‘We shout at each other a lot’

In a small studio in east London, two musicians are doing unspeakable things to a collection of vintage instruments.

Joe Henson and Alexis Smith - aka The Flight - are recording the music for a battle scene in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and it’s making them angry.

“We shout at each other a lot,” says Joe. “It’s a pretty intense thing, writing fight music, both physically and mentally.”

Alexis Smith

The game is set in Ancient Greece, so the duo are bashing low-frame drums and abusing a gut string rebec as they try to replicate the sounds of the period.

Over the course of a day, they record nearly a dozen different versions of the music, trying out low and high-intensity arrangements.

“No, play this!” Joe shouts. “More like that!”

‘We shout at each other a lot’

In a small studio in east London, two musicians are doing unspeakable things to a collection of vintage instruments.

Joe Henson and Alexis Smith - aka The Flight - are recording the music for a battle scene in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and it’s making them angry.

“We shout at each other a lot,” says Joe. “It’s a pretty intense thing, writing fight music, both physically and mentally.”

Alexis Smith

The game is set in Ancient Greece, so the duo are bashing low-frame drums and abusing a gut string rebec as they try to replicate the sounds of the period.

Over the course of a day, they record nearly a dozen different versions of the music, trying out low and high-intensity arrangements.

“No, play this!” Joe shouts. “More like that!”

If Assassin’s Creed were a film (for the sake of this article, we’ll ignore the Hollywood adaptation, just like audiences did), The Flight’s spittle-flecked jam session would result in a single, polished track - timed to perfection with the action on screen and building to a climax as the protagonist finishes off a bad guy with a round kick to the face.

But games composers don’t have the luxury of knowing how a fight will go down.

The player could dispatch an entire garrison by stealth. Or rush into a melee, swinging an axe around their head and setting the camp on fire. If they’re anything like me, they’ll die 25 times before they get to do either of those things.

The music has to be able to react to all those outcomes and more. So how on earth does it work?

In this instance, The Flight will record dozens of variations on their fight theme - so the game can switch between them on the fly, ramping up the intensity if the fight goes wrong, and dialling it back if you find a way to sneak past the guards.

The fight scene is just one element in Assassin’s Creed’s sprawling story.

To complete the main quest will take more than 50 hours - and there’s music for at least half of that.

If Assassin’s Creed were a film (for the sake of this article, we’ll ignore the Hollywood adaptation, just like audiences did), The Flight’s spittle-flecked jam session would result in a single, polished track - timed to perfection with the action on screen and building to a climax as the protagonist finishes off a bad guy with a round kick to the face.

But games composers don’t have the luxury of knowing how a fight will go down.

The player could dispatch an entire garrison by stealth. Or rush into a melee, swinging an axe around their head and setting the camp on fire. If they’re anything like me, they’ll die 25 times before they get to do either of those things.

The music has to be able to react to all those outcomes and more. So how on earth does it work?

In this instance, The Flight will record dozens of variations on their fight theme - so the game can switch between them on the fly, ramping up the intensity if the fight goes wrong, and dialling it back if you find a way to sneak past the guards.

The fight scene is just one element in Assassin’s Creed’s sprawling story.

To complete the main quest will take more than 50 hours - and there’s music for at least half of that.

The best-selling game of 2018, Red Dead Redemption 2, is even bigger. With more than 180 separate musical cues, it required a team of composers to conjure up the dust and dirt of the American West.

Red Dead Redemption 2

(Rockstar Games)

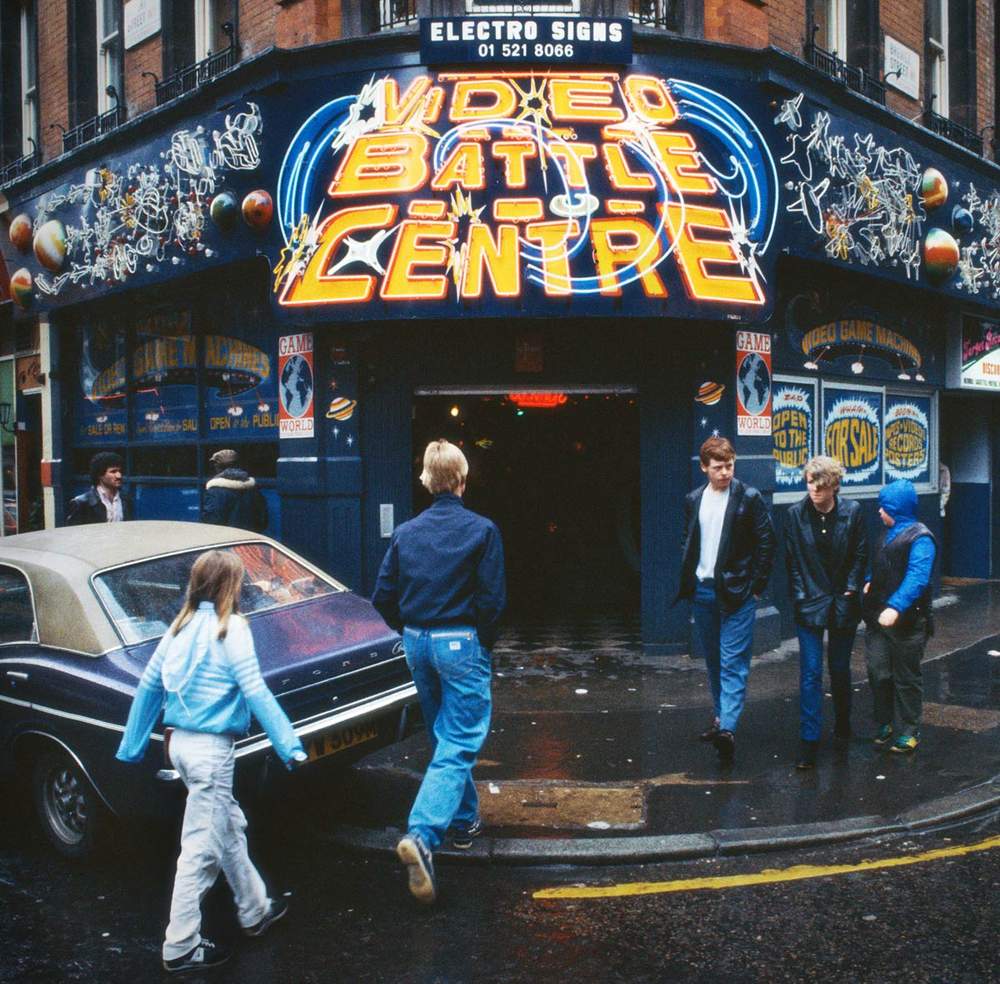

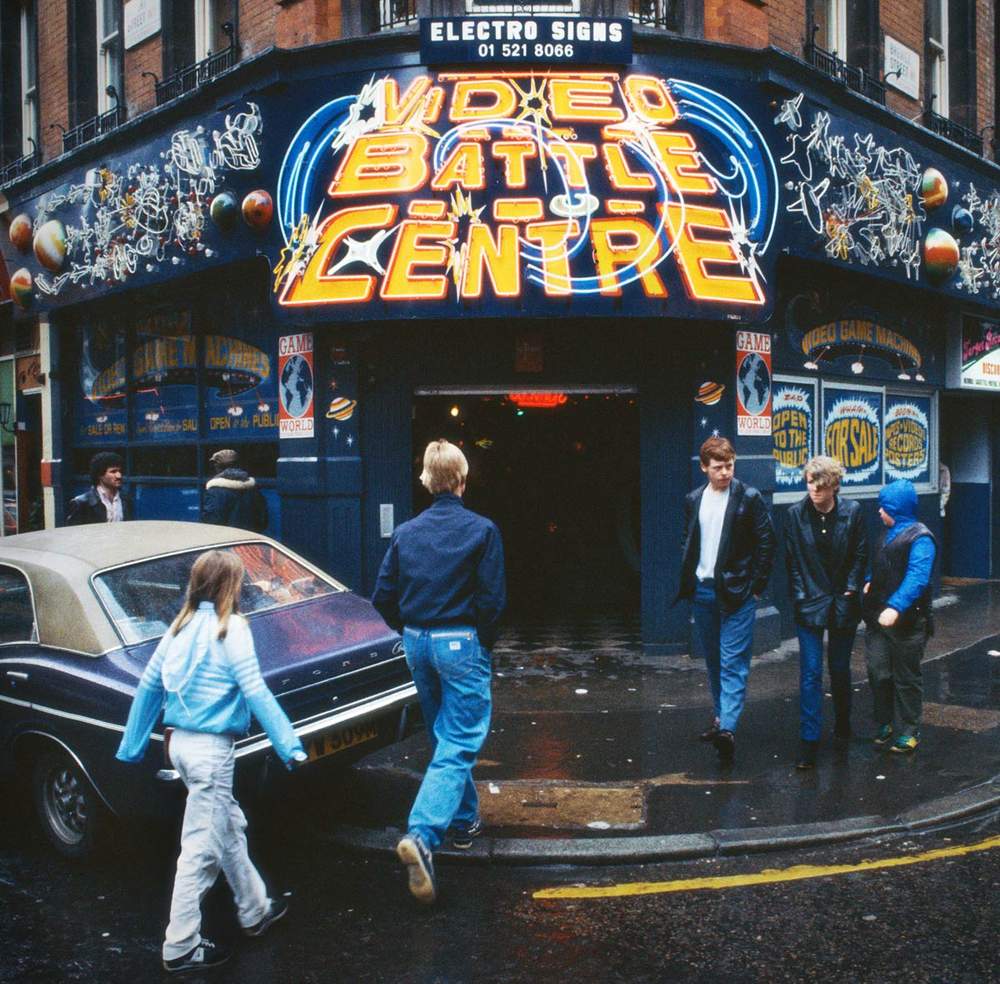

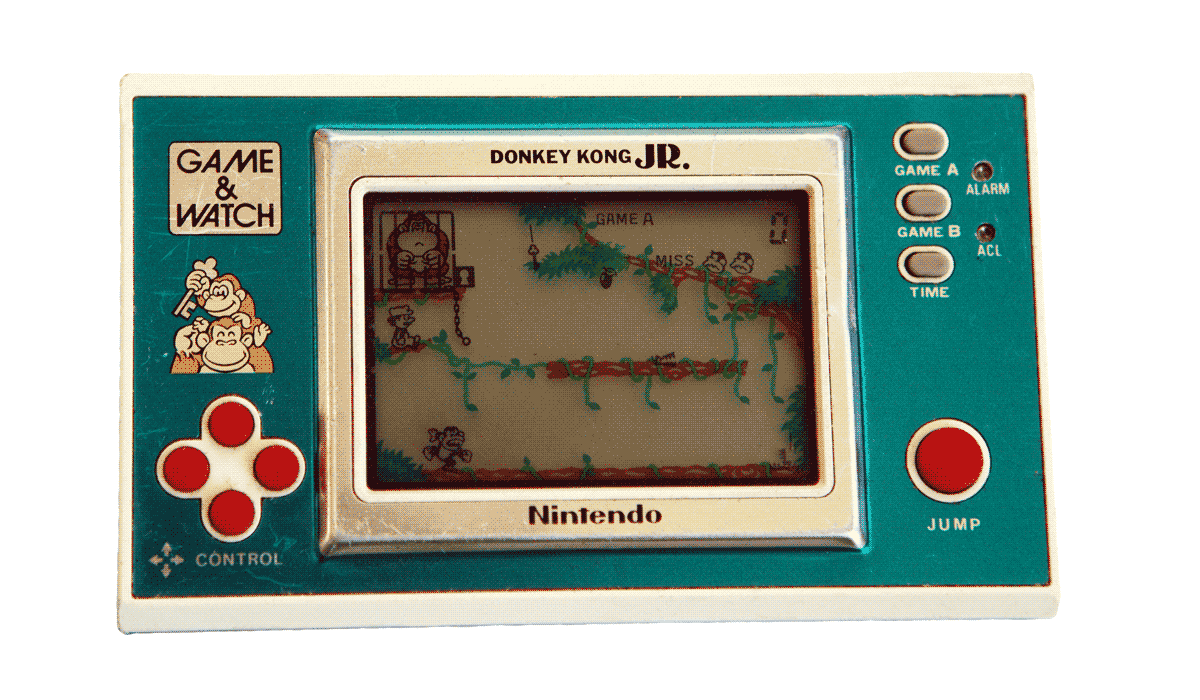

Video game arcade, London, 1979

(Getty Images)

It’s a world away from the simplistic bleeps of 1980s arcade machines, but these epic, multi-layered, orchestral scores are fulfilling the same function as the chiptune sounds of 30-plus years ago.

They’re there to guide, prompt and steer the player.

Repeated themes help you organise and make sense of the game world. And psychologically, things like key and tempo can even affect the way the player perceives time.

Chasing ‘the flow’

Done right, the marriage of music and gameplay can induce a level of immersion that’s impossible in other forms of entertainment.

Known as “the flow”, it’s a state in which “people become so involved in what they are doing that the activity becomes spontaneous, almost automatic,” according to psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who recognised and named the phenomenon.

Players experiencing the flow “stop becoming aware of themselves as separate from the actions they are performing,” he suggests. “And being able to forget temporarily who we are seems to be very enjoyable.”

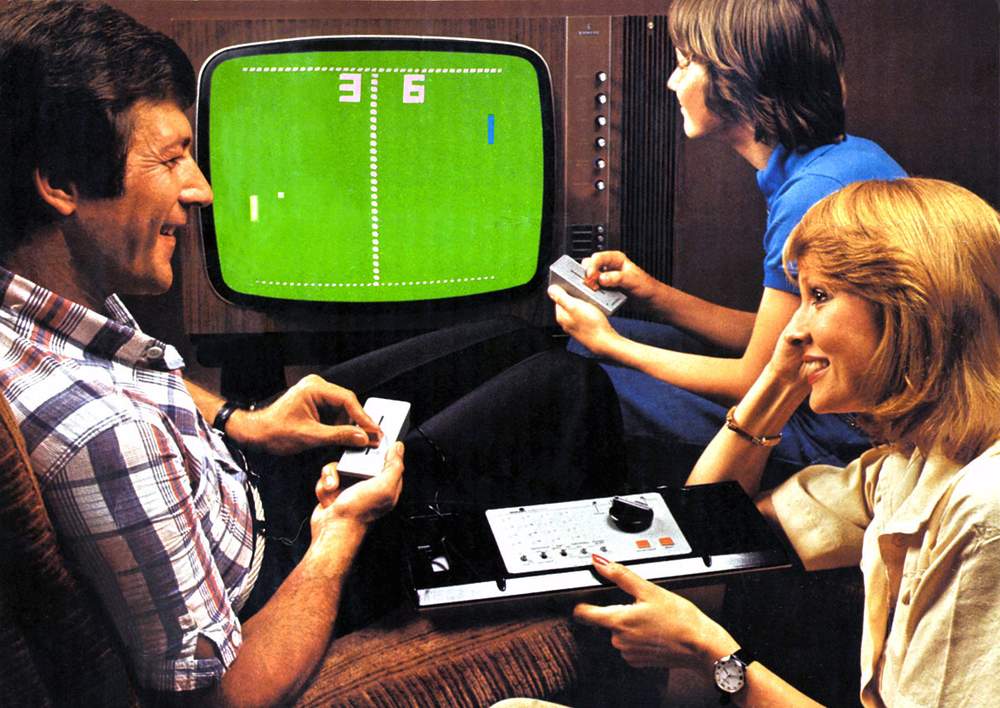

Family playing Pong, 1977

(Alamy)

You might think this is a recent development in gaming. To modern eyes, early arcade cabinets like Pong and Asteroids look too basic to be psychologically transformative - but that’s actually not the case.

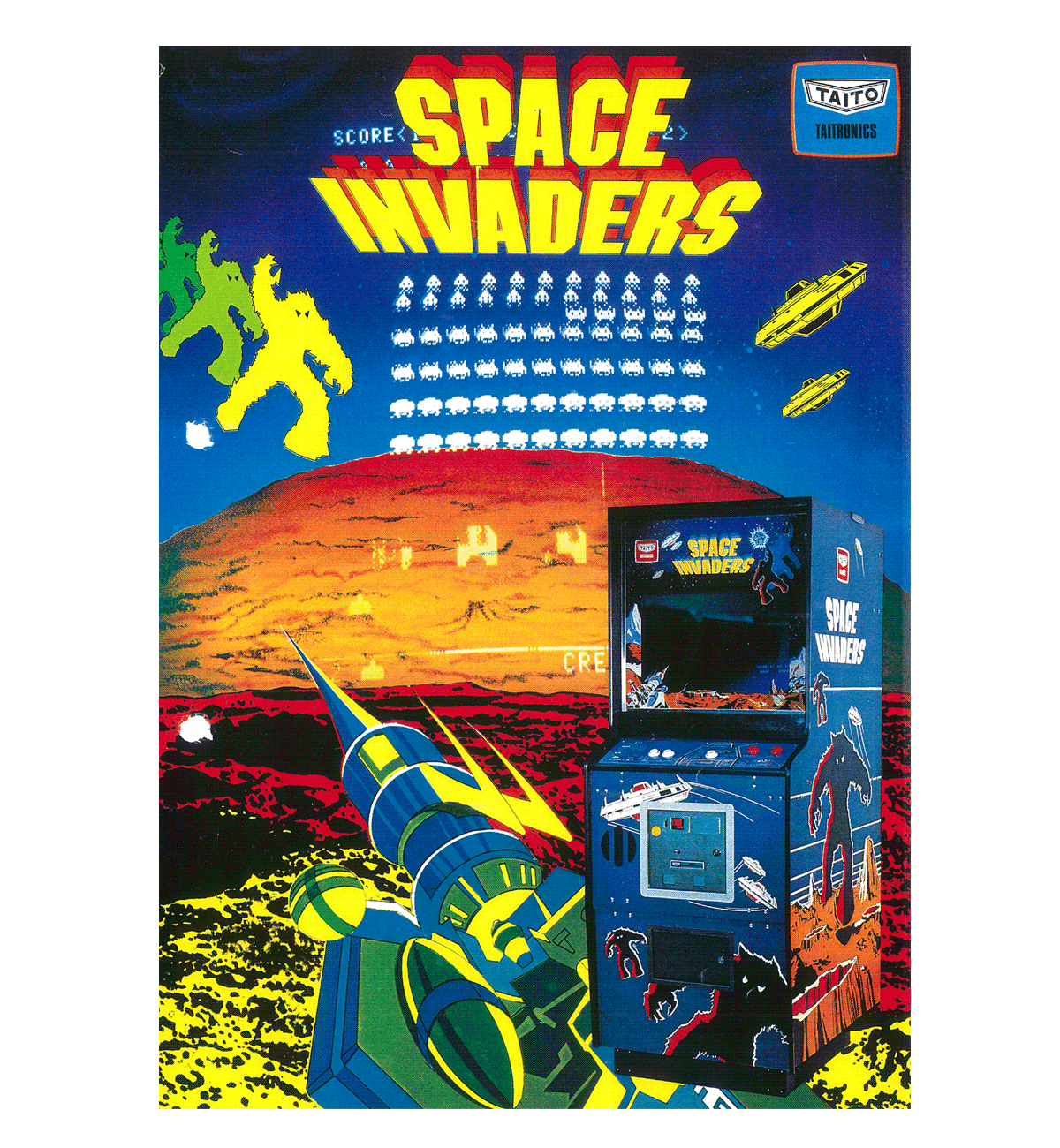

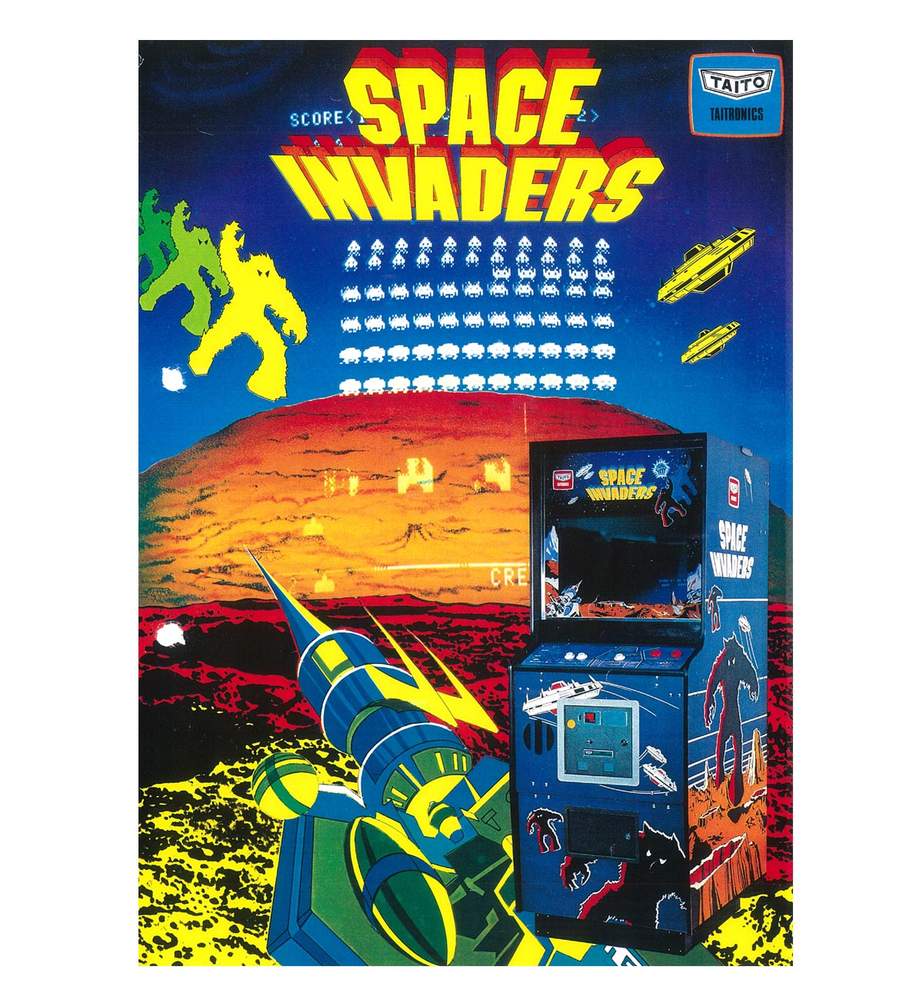

Take Space Invaders.

Released by Taito in 1978, it features a continuous pattern of four descending notes. As music, it’s beyond primitive, but - here’s the clever thing - the melody is initially set to the tempo of an average player’s resting heart rate. As the aliens continue their march towards the humans, it ramps up.

Space Invaders poster

(Taito Corporation)

“The ostinato [repeated musical phrase] gets faster and faster and faster as the situation becomes all the more critical,” says Tim Summers, an expert in ludomusicology - the study of music and play.

“And your heartbeat responds to that - creating a fantastic emotional peak as you play the game.”

Psychologically, challenge is important for catharsis. Victory is sweeter when there’s a clear and looming presence of failure.

But there’s another way to interpret Space Invaders’ escalating tempo.

In the days of coin-operated arcade machines, the programmers also wanted your game to be over quickly so you’d feed another coin into the slot. If the music made you flustered, you’d die more quickly, and they’d make more money.

Space Invaders became so successful that - shortly after its launch - it was blamed for a shortage of 100-yen pieces in Japan (a story that’s been largely debunked).

From that point on, music became an increasingly important part of game development.

Minimalist masterpieces

The early pioneers of game music often had to double up as programmers.

Junko Ozawa, an in-house musician at Namco, remembers having to write the code that powered the custom-built sound chips for games like Gaplus and The Tower of Druaga. Each note would then be painstakingly translated into hexadecimal code and programmed into the game.

What’s more, the sound chips on arcade machines and home consoles like Nintendo’s NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) were generally limited to a few simple tones and one “noise channel” that could be used for percussion and sound effects.

NES (Nintendo Entertainment System)

(Getty Images)

In musical terms, that’s like having two descant recorders, a one-string bass and someone playing a washboard.

“There was very little depth,” recalls Yoko Shimomura, the renowned pianist and composer of Street Fighter II and Kingdom Hearts. “I could only have two sounds - melody and bass.”

The memory available to store music was similarly limited, she adds.

“When I started writing on [Nintendo’s] Super Famicom Disk System, the space I had to create all the music and effects was about 20 megabits (2.5 megabytes), which isn’t even big enough to store a single photograph these days,” she says.

“That meant the music had to be very short. I thought it was impossible but everyone before me was doing it, so I had no choice.”

Working within those limitations, early games composers managed to create some of the genre’s most memorable musical motifs.

Toshio Kai’s minimalist Pac-Man theme was as vibrant and eye-catching as the game itself; while the character’s “waka-waka” sound effect is a perfect musical onomatopoeia.

“It’s an incredible piece of sound design,” says BBC Radio 3’s Tom Service. “Even in a sound that lasts a fraction of a second, you get a musical reward for chomping the pill. It’s a tiny micro-composition that’s giving you a dopamine rush of pleasure and fulfilment.

“It was stunning in the early 80s and it remains so now.”

Sound effects played a crucial role in creating immersive worlds during the early days of gaming.

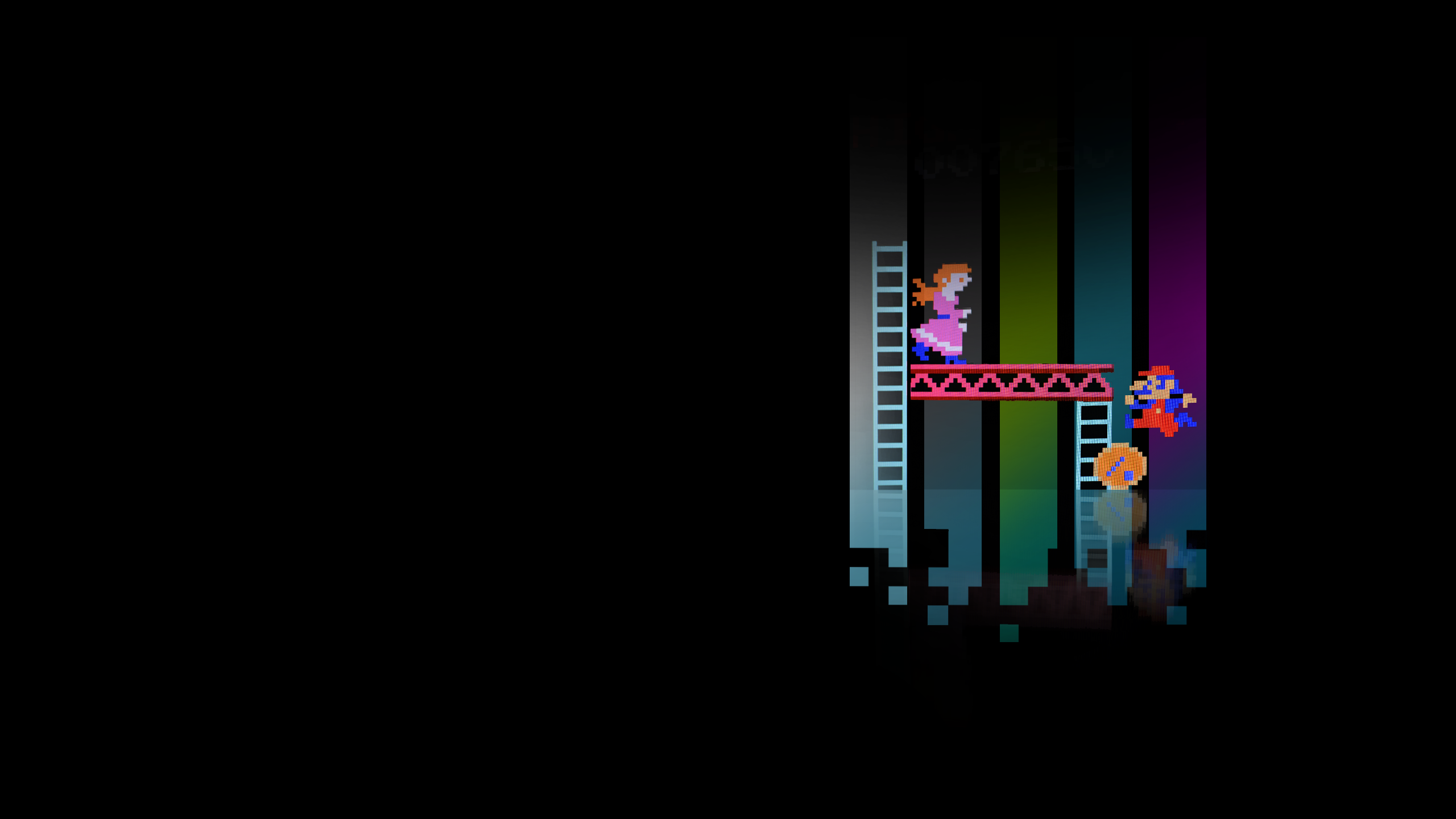

Think of the elastic “poing” as Mario jumps and how it tracks the movement on-screen. Mute the sound and timing the precise jumps you need to clear the level suddenly becomes a lot more difficult.

“In a really good game, the sound effects become part of the soundtrack,” argues journalist and Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker.

“Mario is a brilliant example, where all the sound effects are really satisfying. The coin noise in Mario - I don’t think it’s collecting the coin itself that’s satisfying, it’s the sound it makes that makes some little dopamine detonator go off in your head.

“That’s how they can solve the crisis of newspapers running out of cash. If I had to pay one pence to read every article, and it made that sound, I’d definitely pay to read every article I came across.”

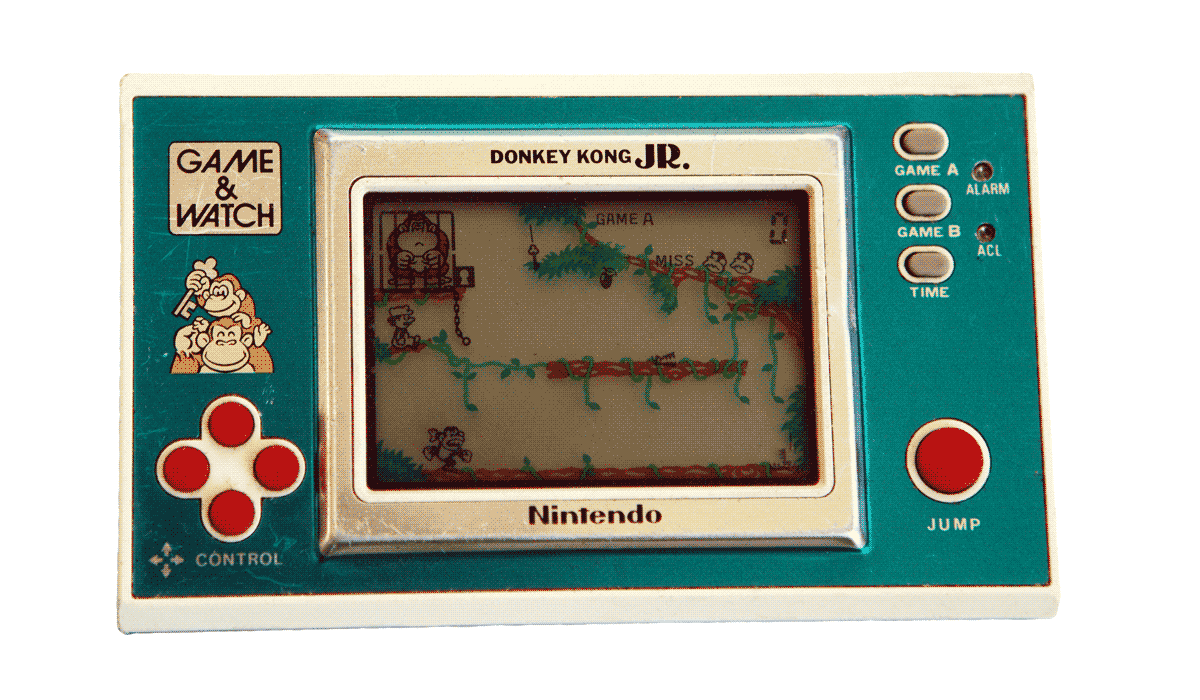

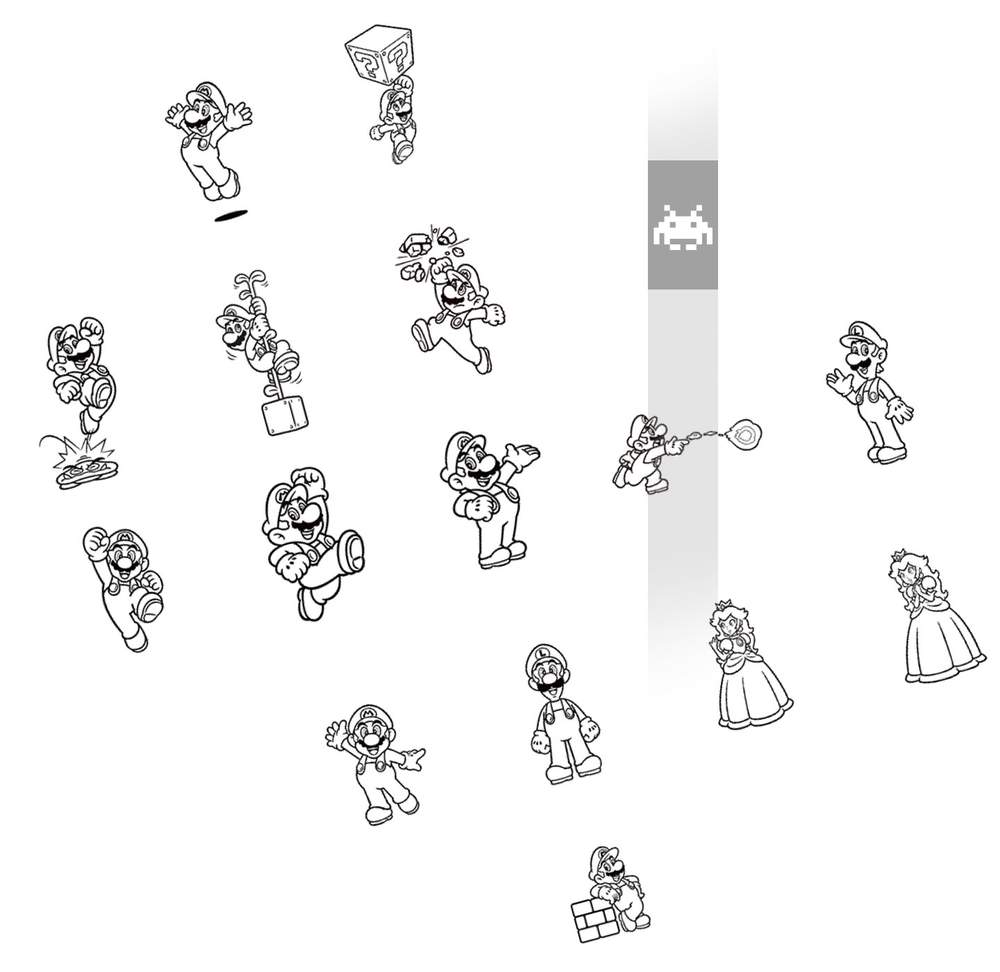

Mario first appeared as "Jumpman" in Donkey Kong

(Alamy)

But Super Mario Bros isn’t just notable for its sound effects. Koji Kondo’s music set a new bar for video game soundtracks, with six songs that were carefully co-ordinated to the movement on-screen.

The music lasts less than three minutes in total, but somehow manages to convey the variety of Princess Peach’s Mushroom Kingdom - from the bouncy, vibrant Overworld Theme to the spooky darkness of its underworld levels.

“I wanted to create something that had never been heard before, where you'd think ‘This isn't like game music at all,’” he told Wired magazine in 2007.

“First off, it had to fit the game the best, enhance the gameplay and make it more enjoyable. Not just sit there and be something that plays while you play the game, but is actually a part of the game.”

Super Mario Bros

(Nintendo)

“When I came across Super Mario for the first time, I was gobsmacked,” says Yoko Shimomura.

“I was playing the game, but the music stayed in me. I wondered why the music could do this. That was when I started realising there was a job in making music for video games. My eyes were opened.”

“It’s the computer gaming equivalent of a mono mix of a Beatles track,” says Charlie Brooker, “where they’re having to record something with rudimentary equipment, and as a result you get something with a White Stripes aesthetic, of a very boiled-down, simplified theme.”

Red Dead Redemption 2

(Rockstar Games)

The best-selling game of 2018, Red Dead Redemption 2, is even bigger.

With more than 180 separate musical cues, it required a team of composers to conjure up the dust and dirt of the American West.

It’s a world away from the simplistic bleeps of 1980s arcade machines, but these epic, multi-layered, orchestral scores are fulfilling the same function as the chiptune sounds of 30-plus years ago.

Video game arcade, London, 1979

(Getty Images)

They’re there to guide, prompt and steer the player.

Repeated themes help you organise and make sense of the game world. And psychologically, things like key and tempo can even affect the way the player perceives time.

Chasing ‘the flow’

Done right, the marriage of music and gameplay can induce a level of immersion that’s impossible in other forms of entertainment.

Known as “the flow”, it’s a state in which “people become so involved in what they are doing that the activity becomes spontaneous, almost automatic,” according to psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who recognised and named the phenomenon.

Players experiencing the flow “stop becoming aware of themselves as separate from the actions they are performing,” he suggests. “And being able to forget temporarily who we are seems to be very enjoyable.”

Family playing Pong, 1977

(Alamy)

You might think this is a recent development in gaming. To modern eyes, early arcade cabinets like Pong and Asteroids look too basic to be psychologically transformative - but that’s actually not the case.

Take Space Invaders.

Released by Taito in 1978, it features a continuous pattern of four descending notes. As music, it’s beyond primitive, but - here’s the clever thing - the melody is initially set to the tempo of an average player’s resting heart rate. As the aliens continue their march towards the humans, it ramps up.

Space Invaders poster

(Taito Corporation)

“The ostinato [repeated musical phrase] gets faster and faster and faster as the situation becomes all the more critical,” says Tim Summers, an expert in ludomusicology - the study of music and play.

“And your heartbeat responds to that - creating a fantastic emotional peak as you play the game.”

Psychologically, challenge is important for catharsis. Victory is sweeter when there’s a clear and looming presence of failure.

But there’s another way to interpret Space Invaders’ escalating tempo.

In the days of coin-operated arcade machines, the programmers also wanted your game to be over quickly so you’d feed another coin into the slot. If the music made you flustered, you’d die more quickly, and they’d make more money.

Space Invaders became so successful that - shortly after its launch - it was blamed for a shortage of 100-yen pieces in Japan (a story that’s been largely debunked).

From that point on, music became an increasingly important part of game development.

Minimalist masterpieces

The early pioneers of game music often had to double up as programmers.

Junko Ozawa, an in-house musician at Namco, remembers having to write the code that powered the custom-built sound chips for games like Gaplus and The Tower of Druaga. Each note would then be painstakingly translated into hexadecimal code and programmed into the game.

What’s more, the sound chips on arcade machines and home consoles like Nintendo’s NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) were generally limited to a few simple tones and one “noise channel” that could be used for percussion and sound effects.

NES (Nintendo Entertainment System)

(Getty Images)

In musical terms, that’s like having two descant recorders, a one-string bass and someone playing a washboard.

“There was very little depth,” recalls Yoko Shimomura, the renowned pianist and composer of Street Fighter II and Kingdom Hearts. “I could only have two sounds - melody and bass.”

The memory available to store music was similarly limited, she adds.

“When I started writing on [Nintendo’s] Super Famicom Disk System, the space I had to create all the music and effects was about 20 megabits (2.5 megabytes), which isn’t even big enough to store a single photograph these days,” she says.

“That meant the music had to be very short. I thought it was impossible but everyone before me was doing it, so I had no choice.”

Working within those limitations, early games composers managed to create some of the genre’s most memorable musical motifs.

Toshio Kai’s minimalist Pac-Man theme was as vibrant and eye-catching as the game itself; while the character’s “waka-waka” sound effect is a perfect musical onomatopoeia.

“It’s an incredible piece of sound design,” says BBC Radio 3’s Tom Service. “Even in a sound that lasts a fraction of a second, you get a musical reward for chomping the pill. It’s a tiny micro-composition that’s giving you a dopamine rush of pleasure and fulfilment.

“It was stunning in the early 80s and it remains so now.”

Sound effects played a crucial role in creating immersive worlds during the early days of gaming.

Think of the elastic “poing” as Mario jumps and how it tracks the movement on-screen. Mute the sound and timing the precise jumps you need to clear the level suddenly becomes a lot more difficult.

“In a really good game, the sound effects become part of the soundtrack,” argues journalist and Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker.

“Mario is a brilliant example, where all the sound effects are really satisfying. The coin noise in Mario - I don’t think it’s collecting the coin itself that’s satisfying, it’s the sound it makes that makes some little dopamine detonator go off in your head.

“That’s how they can solve the crisis of newspapers running out of cash. If I had to pay one pence to read every article, and it made that sound, I’d definitely pay to read every article I came across.”

Mario first appeared as "Jumpman" in Donkey Kong

(Alamy)

But Super Mario Bros isn’t just notable for its sound effects. Koji Kondo’s music set a new bar for video game soundtracks, with six songs that were carefully co-ordinated to the movement on-screen.

The music lasts less than three minutes in total, but somehow manages to convey the variety of Princess Peach’s Mushroom Kingdom - from the bouncy, vibrant Overworld Theme to the spooky darkness of its underworld levels.

“I wanted to create something that had never been heard before, where you'd think ‘This isn't like game music at all,’” he told Wired magazine in 2007.

“First off, it had to fit the game the best, enhance the gameplay and make it more enjoyable. Not just sit there and be something that plays while you play the game, but is actually a part of the game.”

Super Mario Bros

(Nintendo)

“When I came across Super Mario for the first time, I was gobsmacked,” says Yoko Shimomura.

“I was playing the game, but the music stayed in me. I wondered why the music could do this. That was when I started realising there was a job in making music for video games. My eyes were opened.”

“It’s the computer gaming equivalent of a mono mix of a Beatles track,” says Charlie Brooker, “where they’re having to record something with rudimentary equipment, and as a result you get something with a White Stripes aesthetic, of a very boiled-down, simplified theme.”

Enter the blue hedgehog

In the late 80s, computers like the Commodore Amiga and consoles such as the Sega Mega Drive started to feature more advanced sound chips, liberating games composers from many of the constraints they’d been facing.

The sound chip on the Mega Drive was derived from the legendary Yamaha DX7 synthesiser - which meant games suddenly had access to the sounds that appeared in chart hits - like A-ha’s Take On Me and Tears For Fears’ Shout.

To write the music for the console’s flagship game, Sonic the Hedgehog, Sega hired J-pop star Masato Nakamura - who deliberately distanced himself from the 8-bit, chiptune sounds that had become the medium’s distinguishing characteristics.

“At the time, MTV and films were very popular,” he told Video Game Music Online in 2011. “There were a bunch of hit songs, like those from Top Gun, Flashdance, and Dirty Dancing. So I wanted to write songs like that for Sonic the Hedgehog as a film.”

The success of Sonic proved games could compete with pop music and suddenly the floodgates opened.Yuzo Koshiro introduced house and techno to the soundtracks for The Revenge of Shinobi and Streets of Rage - while Yoko Shimomura’s music for Street Fighter II became a hip-hop staple, sampled by Frank Ocean, Nicki Minaj, Kanye West, and Dizzee Rascal.

Sensing this shift, some pop artists started to get involved in game composition.

Trent Reznor wrote the unsettling score for PC shooter Quake, David Bowie cropped up in the adventure game The Nomad Soul and Michael Jackson, who’d worked with Sega on the Moonwalker arcade game that accompanied his film of the same name, got involved with scoring Sonic the Hedgehog 3 (his contributions were largely abandoned, but fans have found fragments of songs like Jam and Stranger In Moscow hidden in the Sonic soundtrack).

Enter the blue hedgehog

In the late 80s, computers like the Commodore Amiga and consoles such as the Sega Mega Drive started to feature more advanced sound chips, liberating games composers from many of the constraints they’d been facing.

The sound chip on the Mega Drive was derived from the legendary Yamaha DX7 synthesiser - which meant games suddenly had access to the sounds that appeared in chart hits - like A-ha’s Take On Me and Tears For Fears’ Shout.

To write the music for the console’s flagship game, Sonic the Hedgehog, Sega hired J-pop star Masato Nakamura - who deliberately distanced himself from the 8-bit, chiptune sounds that had become the medium’s distinguishing characteristics.

“At the time, MTV and films were very popular,” he told Video Game Music Online in 2011.

“There were a bunch of hit songs, like those from Top Gun, Flashdance, and Dirty Dancing. So I wanted to write songs like that for Sonic the Hedgehog as a film.”

The success of Sonic proved games could compete with pop music and suddenly the floodgates opened.

Yuzo Koshiro introduced house and techno to the soundtracks for The Revenge of Shinobi and Streets of Rage - while Yoko Shimomura’s music for Street Fighter II became a hip-hop staple, sampled by Frank Ocean, Nicki Minaj, Kanye West, and Dizzee Rascal.

Sensing this shift, some pop artists started to get involved in game composition.

Trent Reznor wrote the unsettling score for PC shooter Quake, David Bowie cropped up in the adventure game The Nomad Soul and Michael Jackson, who’d worked with Sega on the Moonwalker arcade game that accompanied his film of the same name, got involved with scoring Sonic the Hedgehog 3 (his contributions were largely abandoned, but fans have found fragments of songs like Jam and Stranger In Moscow hidden in the Sonic soundtrack).

Introducing interactivity - vertical or horizontal?

While the Sonic palette available to games composers had improved, the music itself was still linear - playing alongside the action, rather than reacting to it. If a musical cue “pinged” when the player “ponged”, it was through serendipity, not design.

Adaptive scores - where the music players hear changes to match their gameplay - finally arrived in the 1990s.

There were two different, but complementary techniques.

The simplest is known as vertical re-orchestration. It works like an episode of Classic Albums where someone from Fleetwood Mac sits behind a mixing desk and shows off the isolated vocals for Go Your Own Way.

The game essentially takes control of the mixing desk, sliding the faders up and down depending on what’s happening on screen.

“It’s actually not that hard,” says Grant Kirkhope, who first used the trick on the Nintendo 64 games GoldenEye and Banjo-Kazooie.

GoldenEye on the Nintendo 64

(Getty Images)

He explains how he used Midi (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) files - a kind of digital sheet music - to create the illusion of music “following” the player around the game.

“In a Midi file, you get 16 channels, so you can have 16 instruments. So when I’d write the tunes, I’d find out what areas the design guys would want to have in each level, and I’d allocate a certain amount of instruments to each area,” says Kirkhope.

“Then we’d draw circles on the map, which the player can’t see, they’re hidden away, but when the player crosses that line, it signals to the audio engine to fade down, say, channels one, three and six and turn up two, four and eight.

“If you listened to the raw Midi file, you’d hear all the instruments at once, but the game controls which ones you hear at any one time.”

This technique is still used in games today - albeit with full orchestral recordings, rather than synthesised ones.

A more ambitious approach debuted on 1991’s The Secret Of Monkey Island 2 - a point-and-click adventure on the PC and Amiga.

Using the patented iMUSE (Interactive Music Streaming Engine) system, Michael Land and Peter McConnell created a branching musical score that could react dynamically to the player’s choices.

It’s apparent right from the start, when the ornately named protagonist, Guybrush Threepwood, wanders around the small town of Woodtick. Every time he enters a building or encounters a new character, the game introduces a variation on the main theme.

When he wakes up a group of sleeping pirates, for example, a jaunty accordion picks up the melody. As he walks away, the pirates’ theme ends with a flourish, before segueing seamlessly back to the overture.

The technique is called horizontal re-sequencing, and it works by putting “triggers” into the Midi files that contain the musical score. When a specific action occurs, the game jumps to the appropriate section of the song - as if the player is James Brown, telling the computer to “take it to the bridge”.

For the musician, though, horizontal resequencing presents a huge conceptual headache.

“You essentially have to take the core storytelling aspects of music composition and break them apart as if they’re all cards in a deck,” says Winifred Phillips, author of A Composer’s Guide To Game Music.

“You could be pulling any one of those cards at any particular time, and it has to be able to work on its own. So that unravels your brain as a composer. You’ve got to unlearn all the narrative aspects of composition that you’ve been taught.

“It’s challenging, it’s interesting, and it’s something composers and game teams are still exploring. And the more we explore, the more interesting gameplay becomes.”

Introducing interactivity - vertical or horizontal?

While the Sonic palette available to games composers had improved, the music itself was still linear - playing alongside the action, rather than reacting to it. If a musical cue “pinged” when the player “ponged”, it was through serendipity, not design.

Adaptive scores - where the music players hear changes to match their gameplay - finally arrived in the 1990s.

There were two different, but complementary techniques.

The simplest is known as vertical re-orchestration. It works like an episode of Classic Albums where someone from Fleetwood Mac sits behind a mixing desk and shows off the isolated vocals for Go Your Own Way.

The game essentially takes control of the mixing desk, sliding the faders up and down depending on what’s happening on screen.

“It’s actually not that hard,” says Grant Kirkhope, who first used the trick on the Nintendo 64 games GoldenEye and Banjo-Kazooie.

GoldenEye on the Nintendo 64

(Getty Images)

He explains how he used Midi (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) files - a kind of digital sheet music - to create the illusion of music “following” the player around the game.

“In a Midi file, you get 16 channels, so you can have 16 instruments. So when I’d write the tunes, I’d find out what areas the design guys would want to have in each level, and I’d allocate a certain amount of instruments to each area,” says Kirkhope.

“Then we’d draw circles on the map, which the player can’t see, they’re hidden away, but when the player crosses that line, it signals to the audio engine to fade down, say, channels one, three and six and turn up two, four and eight.

“If you listened to the raw Midi file, you’d hear all the instruments at once, but the game controls which ones you hear at any one time.”

This technique is still used in games today - albeit with full orchestral recordings, rather than synthesised ones.

A more ambitious approach debuted on 1991’s The Secret Of Monkey Island 2 - a point-and-click adventure on the PC and Amiga.

Using the patented iMUSE (Interactive Music Streaming Engine) system, Michael Land and Peter McConnell created a branching musical score that could react dynamically to the player’s choices.

It’s apparent right from the start, when the ornately named protagonist, Guybrush Threepwood, wanders around the small town of Woodtick. Every time he enters a building or encounters a new character, the game introduces a variation on the main theme.

When he wakes up a group of sleeping pirates, for example, a jaunty accordion picks up the melody. As he walks away, the pirates’ theme ends with a flourish, before segueing seamlessly back to the overture.

The technique is called horizontal re-sequencing, and it works by putting “triggers” into the Midi files that contain the musical score. When a specific action occurs, the game jumps to the appropriate section of the song - as if the player is James Brown, telling the computer to “take it to the bridge”.

For the musician, though, horizontal resequencing presents a huge conceptual headache.

“You essentially have to take the core storytelling aspects of music composition and break them apart as if they’re all cards in a deck,” says Winifred Phillips, author of A Composer’s Guide To Game Music.

“You could be pulling any one of those cards at any particular time, and it has to be able to work on its own. So that unravels your brain as a composer. You’ve got to unlearn all the narrative aspects of composition that you’ve been taught.

“It’s challenging, it’s interesting, and it’s something composers and game teams are still exploring. And the more we explore, the more interesting gameplay becomes.”

No Man’s Sky: An infinite soundtrack

Taken to its most complex extreme, horizontal resequencing takes a grab-bag of musical components and puts them together like Tetris blocks as you play, creating an entirely unpredictable, dynamic score.

Glam-prog-ambient-techno genius Brian Eno took just that approach with The Shuffler - a piece of software that created a constantly mutating score for 2007’s ambitious-yet-flawed evolution adventure Spore.

A more recent application came in Hello Games’ space adventure, No Man’s Sky, which was released in 2016 for the PlayStation 4.

No Man’s Sky: An infinite soundtrack

Taken to its most complex extreme, horizontal resequencing takes a grab-bag of musical components and puts them together like Tetris blocks as you play, creating an entirely unpredictable, dynamic score.

Glam-prog-ambient-techno genius Brian Eno took just that approach with The Shuffler - a piece of software that created a constantly mutating score for 2007’s ambitious-yet-flawed evolution adventure Spore.

A more recent application came in Hello Games’ space adventure, No Man’s Sky, which was released in 2016 for the PlayStation 4.

An astounding technological feat, the on-screen game algorithmically generates everything that exists in its vast, freeform universe.

Plants, planets, alien lifeforms and environments are all randomised, with a theoretical 18 quintillion worlds for the player to visit and, perhaps, conquer.

No Man's Sky

(Hello Games)

The music is no less ambitious. Created by Sheffield math-rock band 65daysofstatic, it’s a progressive, experimental suite of songs that changes every time it’s played… with almost infinite variations.

“The only brief we got was: ‘Don’t write a soundtrack, write a 65daysofstatic record, because that’s the sound we want. Oh, by the way, we’re going to make it into an infinite soundtrack, but don’t worry about that. We’ll sort it out,’” says guitarist Paul Wolinski.

Intrigued, the band started to investigate generative music - and discovered it mostly consisted of bland, ambient soundscapes - because it’s easier to fuse several disparate musical elements if you don’t have to bother with drum beats and vocal melodies, where sudden changes are all-too noticeable.

“We wanted to try and overcome that,” says Wolinksi.

“So we actually started writing in a pretty traditional way. We wrote the big tunes and the big melodies. But what normally happens in our writing process is a lot of stuff gets left behind.

But for No Man’s Sky, instead of mercilessly throwing that stuff away, we started libraries of melodies and drum kit samples and guitar lines for every single song.”

In total, they created more than 30 hours of raw audio - from 50 takes of a single guitar note, to sprawling, expansive washes of synth chords.

“Each of those tracks had rules and logic attached to it. Then it was all tied to one big dial [inside the game’s bespoke audio engine], which was interest level,” Wolinski explains.

“So if more interesting things happen, then the music would rise up to meet that interest.”

This generative music is still an experimental artform - and one that requires a whole new approach. But Wolinski is optimistic about the future.

“There’s a vast unexplored terrain. There’s going to be so much advancement over the next few years, I’m really excited about it. And I think No Man’s Sky will be looked back on as a bit of a landmark - as a brave, foolhardy step into this unknown territory.”

Even on more traditional soundtracks, composers are breaking new ground.

One of The Flight’s most recent jobs was to create a sound-world for the PS4 game Horizon Zero Dawn.

Set on a post-apocalyptic Earth, where humanity has had to rebuild itself, the game required the duo to invent an entirely new form of music.

“They said to us that they didn’t want it to sound like anything else that had ever been made musically, which is a challenge,” says Alexis Smith.

“And one of the things they said was they didn’t want us to use real strings - but the thing a string section does in music is very useful - it portrays emotions very easily.

“So Joe invented what we call the Horizon Orchestra, which is lots of layered harmonicas with lots of bowed guitars on top. Tracking that all up, gave us the same… it does the job a string section does, without sounding like anything that’s been done before.”

An astounding technological feat, the on-screen game algorithmically generates everything that exists in its vast, freeform universe.

Plants, planets, alien lifeforms and environments are all randomised, with a theoretical 18 quintillion worlds for the player to visit and, perhaps, conquer.

No Man's Sky

(Hello Games)

The music is no less ambitious. Created by Sheffield math-rock band 65daysofstatic, it’s a progressive, experimental suite of songs that changes every time it’s played… with almost infinite variations.

“The only brief we got was: ‘Don’t write a soundtrack, write a 65daysofstatic record, because that’s the sound we want. Oh, by the way, we’re going to make it into an infinite soundtrack, but don’t worry about that. We’ll sort it out,’” says guitarist Paul Wolinski.

Intrigued, the band started to investigate generative music - and discovered it mostly consisted of bland, ambient soundscapes - because it’s easier to fuse several disparate musical elements if you don’t have to bother with drum beats and vocal melodies, where sudden changes are all-too noticeable.

“We wanted to try and overcome that,” says Wolinksi. “So we actually started writing in a pretty traditional way. We wrote the big tunes and the big melodies. But what normally happens in our writing process is a lot of stuff gets left behind. But for No Man’s Sky, instead of mercilessly throwing that stuff away, we started libraries of melodies and drum kit samples and guitar lines for every single song.”

In total, they created more than 30 hours of raw audio - from 50 takes of a single guitar note, to sprawling, expansive washes of synth chords.

“Each of those tracks had rules and logic attached to it. Then it was all tied to one big dial [inside the game’s bespoke audio engine], which was interest level,” Wolinski explains.

“So if more interesting things happen, then the music would rise up to meet that interest.”

This generative music is still an experimental artform - and one that requires a whole new approach. But Wolinski is optimistic about the future.

“There’s a vast unexplored terrain. There’s going to be so much advancement over the next few years, I’m really excited about it. And I think No Man’s Sky will be looked back on as a bit of a landmark - as a brave, foolhardy step into this unknown territory.”

Even on more traditional soundtracks, composers are breaking new ground.

One of The Flight’s most recent jobs was to create a sound-world for the PS4 game Horizon Zero Dawn.

Set on a post-apocalyptic Earth, where humanity has had to rebuild itself, the game required the duo to invent an entirely new form of music.

“They said to us that they didn’t want it to sound like anything else that had ever been made musically, which is a challenge,” says Alexis Smith.

“And one of the things they said was they didn’t want us to use real strings - but the thing a string section does in music is very useful - it portrays emotions very easily.

“So Joe invented what we call the Horizon Orchestra, which is lots of layered harmonicas with lots of bowed guitars on top. Tracking that all up, gave us the same… it does the job a string section does, without sounding like anything that’s been done before.”

Musical manipulation

So games composers face problems - and opportunities - that no other musician ever has to think about. But the goal is always the same.

“More than anything else, we are holding the player’s hand,” says Jessica Curry, the Bafta-winning composer of Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture.

“That’s really important to remember - the player is at the centre of this experience. We are trying to guide them without pushing them. I never want the player to feel like I forced them in a certain direction. I want to give them time to think, to dream, to contemplate, to form their own conclusions about what’s happening in the story.”

Nonetheless, there are ways the composer can manipulate the player. “You can affect the speed somebody walks quite drastically,” laughs The Flight’s Joe Henson.

“We don’t really tell players what to do,” says Inon Zur, the Israeli composer behind the Fallout series. “It’s more about what they should feel. So let’s say we are in a certain situation - it’s a very dark night - we can tell them through the music, ‘Hey, help is on the way’.

“So it’s not always about what’s happening now, it’s about how we want the player to feel. And based on their feeling, they will prepare and move to the next step.”

Achieving that can require acute problem-solving skills - as Winifred Phillips discovered when she worked on SimAnimals.

SimAnimals

(Electronic Arts)

“SimAnimals is a strategy game - and those kinds of strategy games require players to spread their consciousness out and be aware of a lot of simultaneous activities across the screen; to make judgements about what to pay attention to, what to file in the back of their minds for later.

“Early on in the development, I had conversations with the development team and they were thinking more of a lyrical, melodic score. Something almost Disney-esque - and that made sense because this is a story about caring for woodland animals and nurturing them and seeing them grow.

“But as we created test pieces, it just really didn’t gel with the gameplay. And that really didn’t make sense, so we had to experiment quite a bit to try and make this work.”

The solution, she discovered, lay with the minimalist and post-minimalist works of Philip Glass, Steve Reich and John Adams.

“That kind of music is structured around lots of simultaneous small activity that relates and yet is separate, and develops in subtle ways, and is almost mathematical in its structure, so it affects the way players think when they’re playing strategy games.”

In fact, a lot of game music is counter-intuitive.

For example, did you know that fast, uptempo songs make time seem to pass more slowly? That’s one reason why racing games like Wipeout and Need For Speed use high-octane dance music - because it’s actually improving your response times.

Musical manipulation

So games composers face problems - and opportunities - that no other musician ever has to think about. But the goal is always the same.

“More than anything else, we are holding the player’s hand,” says Jessica Curry, the Bafta-winning composer of Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture.

“That’s really important to remember - the player is at the centre of this experience. We are trying to guide them without pushing them. I never want the player to feel like I forced them in a certain direction. I want to give them time to think, to dream, to contemplate, to form their own conclusions about what’s happening in the story.”

Nonetheless, there are ways the composer can manipulate the player. “You can affect the speed somebody walks quite drastically,” laughs The Flight’s Joe Henson.

“We don’t really tell players what to do,” says Inon Zur, the Israeli composer behind the Fallout series. “It’s more about what they should feel. So let’s say we are in a certain situation - it’s a very dark night - we can tell them through the music, ‘Hey, help is on the way’.

“So it’s not always about what’s happening now, it’s about how we want the player to feel. And based on their feeling, they will prepare and move to the next step.”

Achieving that can require acute problem-solving skills - as Winifred Phillips discovered when she worked on SimAnimals.

SimAnimals

(Electronic Arts)

“SimAnimals is a strategy game - and those kinds of strategy games require players to spread their consciousness out and be aware of a lot of simultaneous activities across the screen; to make judgements about what to pay attention to, what to file in the back of their minds for later.

“Early on in the development, I had conversations with the development team and they were thinking more of a lyrical, melodic score. Something almost Disney-esque - and that made sense because this is a story about caring for woodland animals and nurturing them and seeing them grow.

“But as we created test pieces, it just really didn’t gel with the gameplay. And that really didn’t make sense, so we had to experiment quite a bit to try and make this work.”

The solution, she discovered, lay with the minimalist and post-minimalist works of Philip Glass, Steve Reich and John Adams.

“That kind of music is structured around lots of simultaneous small activity that relates and yet is separate, and develops in subtle ways, and is almost mathematical in its structure, so it affects the way players think when they’re playing strategy games.”

In fact, a lot of game music is counter-intuitive.

For example, did you know that fast, uptempo songs make time seem to pass more slowly? That’s one reason why racing games like Wipeout and Need For Speed use high-octane dance music - because it’s actually improving your response times.

Game Over

But the biggest psychological trick of all comes when you see the Game Over screen.

“Death music is really fascinating,” says ludomusicologist Tim Summers. “It draws on established signifiers of sadness and death - descending lines, a slow or slowing tempo. A lot of it mimics that classic cartoon ‘wah wah wah’ of sadness and failure.

“But death music has to walk a very fine line. It has to make the character’s death and loss significant, but at the same time, it has to encourage you to get back up and press the button to start again.”

“You don’t want to make it too grim,” agrees Grant Kirkhope, whose recent work includes Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle, and Ghostbusters. “We always try and make it a little bit comedic, or not too nasty.”

Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle

(Nintendo)

Back in Shoreditch, The Flight are recording the finale of their Assassin’s Creed battle sequence. Whether the player lives or dies, there’s no fanfare, no funeral march. Instead it’s a long, sedate piece, full of sustained notes on the rebec.

“The key thing here is that you don’t notice the fight stopping so much,” says Joe Henson. “The outro just ebbs away into the background, so you don’t really notice it’s gone - but maybe you feel the tension releasing.”

The outro deliberately avoids suggesting finality - because the game designers don’t want you to switch off the game and go to bed when the fight ends. They’d much rather you spent another four or five hours inhabiting this vast world they’ve built.

“Musically it’s lovely when things peter out and become calm again,” says Joe. “You’re not completely destroyed by the fight.

“As a player you go, ‘Oh, I actually can keep going. I can continue with my quest.’”

‘The last bastion of melody’

From its origins in the arcades, game music has blossomed into a mainstream artform.

Fans snap up the music to Minecraft and Red Dead Redemption on vinyl - while concert halls echo to the sound of Nobuo Uematsu’s Final Fantasy score or Koji Kondo’s Legend of Zelda theme (written, as it happens, in a single night after he discovered Ravel’s Bolero was still in copyright and couldn’t be used).

Gamers play Square Enix's Final Fantasy XV

at the 2016 Tokyo Game Show

(Getty Images)

“I feel like video games are the last bastion protecting melody,” says Grant Kirkhope.

“A lot of big movies don’t hammer it out like they used to - but in video games, we’re constantly told melody, melody, melody.

“When I did that Mario game over the last couple of years, there’s probably two-and-a-half hours of music [and] every single level had a new theme. So I feel like video games are a real home to bona fide leitmotif [recurring] melody.”

“People are absolutely hungry to hear this music,” says Jessica Curry.

“If you think of Final Fantasy or Zelda or Mario, those themes are so embedded in people’s hearts and souls. They’ve accompanied people through births, deaths, funerals.

“So many people write to me now and say, ‘Somebody close to me has died, and I’d love to play your music at the funeral’. That’s how deep this music is going.”

And the relationship between player and composer flows in two directions.

“For a long time, I couldn’t see the people who’d listen to the music,” recalls Yoko Shimomura, “but when I joined [games company] Square Enix they put feedback cards in the game box. People would buy the disc and fill out the card - and a stack of them were eventually brought to my desk.

“When I was struggling, and I thought I was useless and talentless, I’d read those cards and they really empowered me. There were times I read that feedback in the middle of the night and overcame the hardships.

“And now that my music is played by orchestras and I have the ability to go abroad, I got everything I ever wanted. It is just as if I’m half-dreaming.”

Game Over

But the biggest psychological trick of all comes when you see the Game Over screen.

“Death music is really fascinating,” says ludomusicologist Tim Summers. “It draws on established signifiers of sadness and death - descending lines, a slow or slowing tempo. A lot of it mimics that classic cartoon ‘wah wah wah’ of sadness and failure.

“But death music has to walk a very fine line. It has to make the character’s death and loss significant, but at the same time, it has to encourage you to get back up and press the button to start again.”

“You don’t want to make it too grim,” agrees Grant Kirkhope, whose recent work includes Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle, and Ghostbusters. “We always try and make it a little bit comedic, or not too nasty.”

Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle

(Nintendo)

Back in Shoreditch, The Flight are recording the finale of their Assassin’s Creed battle sequence. Whether the player lives or dies, there’s no fanfare, no funeral march. Instead it’s a long, sedate piece, full of sustained notes on the rebec.

“The key thing here is that you don’t notice the fight stopping so much,” says Joe Henson. “The outro just ebbs away into the background, so you don’t really notice it’s gone - but maybe you feel the tension releasing.”

The outro deliberately avoids suggesting finality - because the game designers don’t want you to switch off the game and go to bed when the fight ends. They’d much rather you spent another four or five hours inhabiting this vast world they’ve built.

“Musically it’s lovely when things peter out and become calm again,” says Joe. “You’re not completely destroyed by the fight.

“As a player you go, ‘Oh, I actually can keep going. I can continue with my quest.’”

‘The last bastion of melody’

From its origins in the arcades, game music has blossomed into a mainstream artform.

Fans snap up the music to Minecraft and Red Dead Redemption on vinyl - while concert halls echo to the sound of Nobuo Uematsu’s Final Fantasy score or Koji Kondo’s Legend of Zelda theme (written, as it happens, in a single night after he discovered Ravel’s Bolero was still in copyright and couldn’t be used).

Gamers play Square Enix's Final Fantasy XV

at the 2016 Tokyo Game Show

(Getty Images)

“I feel like video games are the last bastion protecting melody,” says Grant Kirkhope.

“A lot of big movies don’t hammer it out like they used to - but in video games, we’re constantly told melody, melody, melody.

“When I did that Mario game over the last couple of years, there’s probably two-and-a-half hours of music [and] every single level had a new theme. So I feel like video games are a real home to bona fide leitmotif [recurring] melody.”

“People are absolutely hungry to hear this music,” says Jessica Curry.

“If you think of Final Fantasy or Zelda or Mario, those themes are so embedded in people’s hearts and souls. They’ve accompanied people through births, deaths, funerals.

“So many people write to me now and say, ‘Somebody close to me has died, and I’d love to play your music at the funeral’. That’s how deep this music is going.”

And the relationship between player and composer flows in two directions.

“For a long time, I couldn’t see the people who’d listen to the music,” recalls Yoko Shimomura, “but when I joined [games company] Square Enix they put feedback cards in the game box. People would buy the disc and fill out the card - and a stack of them were eventually brought to my desk.

“When I was struggling, and I thought I was useless and talentless, I’d read those cards and they really empowered me. There were times I read that feedback in the middle of the night and overcame the hardships.

“And now that my music is played by orchestras and I have the ability to go abroad, I got everything I ever wanted. It is just as if I’m half-dreaming.”

Want to proceed to the next level and hear what goes into making a modern video game soundtrack?

Listen to 6 Music's History of Video Game Music