You’ve heard Kerry Muzzey’s work (Bandcamp, Spotify), even if you haven’t heard of him. The 50-year-old classical music composer from Joliet, Illinois, who now lives in Los Angeles, produces haunting orchestral scores that soundtrack some of the most poignant moments in film and television. When Finn Hudson kissed Rachel Berry for the first time on TV’s Glee, it was Muzzey’s stripped-back piano playing in the background. Some of his works have been choreographed and performed on So You Think You Can Dance?, too.

The use of Muzzey’s music across pop culture has no doubt brought the veteran composer some success and acclaim. And around 2012, he decided to see for himself, searching for his name on YouTube. Muzzey recalls the site’s algorithm surfaced 20 or 40 videos. The majority were fan compilations that teenagers obsessed with Glee had painstakingly put together to memorialize their two favorite characters' love story—and they were all soundtracked to the full version of Muzzey’s music.

“It was really kind of cool and validating, especially for someone who was a complete independent, to have a kid finding a piece of instrumental music, which is the most uncool kind of music for a kid to find, and to make a tribute montage using it,” he explains. “It was stuff nobody would have a problem with.”

No one had a problem, that is, until a few years later when Muzzey gained access to YouTube’s ContentID system, the platform’s automated copyright tracker.

That handful of Glee fan videos just scratched the surface. Unbeknownst to the composer, waiting beyond a YouTube search for his name was a seeming subindustry that consistently used Muzzey’s music without his knowledge. ContentID surfaced roughly 20,000 videos for Muzzey in the first month—200 or 400 more got flagged every single day.

Many of these works weren’t from amateur obsessives tinkering around with video editing software. Some were annoying but smallscale, like professional wedding videographers who had decided Muzzey’s music was the perfect backing track for a bride’s big day, but they didn’t want to pay for the rights. “Things like that were mildly angering,” he says.

But other video makers clearly should’ve had no issue shelling for a license. There were projects from ad agencies producing spots to hawk bottled water, hotel chains, and car commercials. Yet the thing that annoyed Muzzey the most were the pages upon pages of full TV episodes uploaded to YouTube that returned a positive hit through the ContentID system. They came from all over Asia: Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. China was one of the biggest offenders.

“It was overwhelming,” Muzzey tells Ars about the hours spent poring over the results. The list of offending work was growing so fast that by the time Muzzey had looked at a couple of videos to ensure YouTube’s copyright infringement system wasn’t misfiring, another page of 25 search results had been appended to the end.

A never-ending stream of videos from across the world was evidently co-opting Muzzey’s work. And the list of infringers eventually included one of the world’s biggest TV networks.

Copyright and wrong

Copyright infringement on the Internet is as old as the Internet itself. Lax rules and the free spirit ethos that embodied the early days of the Web made it seem almost acceptable to share illicitly obtained copies of materials with fellow users, and every digitally connected generation since has its own memories of getting files and footage illegally. For early Internet users, IRC channels were one main method; later browsers will still swell with pride when Kazaa or Limewire are mentioned.

Today, those wanting free access to pirated material are spoilt for choice: they can gain access to free books through Lib-Gen; movies and TV shows from sites like Putlocker, illegal streaming services, or through torrents; and Internet users in 2021 can even educate themselves for free. Sci-Hub’s one-woman battle against the tyranny of paid-for access to academic papers means it’s possible to get almost any research paper you could want without handing over a single penny. As the coronavirus whips up a perfect storm of people stuck at home because movie theaters and concert venues are closed, coupled with less disposable income because of the mass ranks of unemployment as a result of the pandemic, piracy is on the rise. There was a 33 percent piracy increase in the US and UK within the first month of lockdown, from February 2020 to March 2020, according to Muso, a company that tracks online piracy.So even today, the Internet is built on a remix and republish ethos—a mantra that has laid waste to copyright and the ability for copyright holders to lay claim to their work. The reason we all log on to YouTube now and not any number of its oddly named competitors like Revver or Vimeo is in part because of the site’s willingness to look the other way about copyrighted material uploaded onto the platform. Notably, a Saturday Night Live skit called Lazy Sunday was one of YouTube’s earliest viral successes.

Of course, YouTube has attempted to clean up its act since. It’s now as much a site for professional production companies to post full TV shows, documentaries, and music videos as it is an online repository for hobbyists with video cameras. ContentID has been praised by those who own the rights to works and lambasted by those who think the commercialism of the site has robbed it of its creative streak. Though Alphabet, parent company of YouTube and Google, doesn’t break down copyright removal requests on YouTube specifically, across Google it received requests to take down content from more than 220,000 individual copyright owners in 2019. (YouTube declined to comment for this story.)

While this copyright system is strong in theory, in practice there are loopholes. “Power asymmetries mean YouTube is not really incentivized to care about an appropriate resolution when problems crop up for individual musicians,” explains Kevin Erickson, director of the Future of Music Coalition, a Washington, DC-based lobby group campaigning for musicians’ rights. That asymmetry means there are still people—companies, even—who get around the system and who think copyright doesn’t work for them.

Surprisingly, global entertainment behemoth China Central Television stands firmly within this copyright-antagonistic group.

Three strikes

China Central Television (CCTV) is a network of dozens of TV channels that broadcasts video content to more than a billion people inside China. As you’d expect from a monolithic media outlet in the centrally controlled Communist state, it’s an arm of the government. The public service broadcaster is nominally like the UK’s BBC or America’s PBS, but in reality it’s closely connected to the Chinese state. And CCTV has repeatedly shown it’s more than happy to breach copyright.

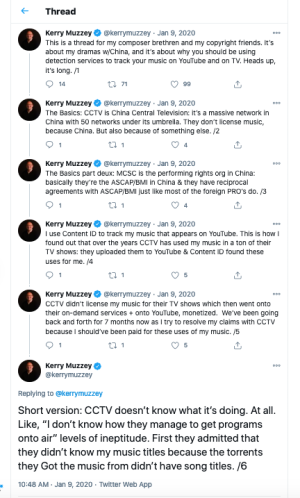

Among the huge numbers of results that Muzzey found when he ran his regular ContentID searches were scores of hits from TV shows broadcast on CCTV. In all, he found 17 TV programs and movies emanating from CCTV that used some of his music. Some of those videos weren’t posted by official CCTV channels; instead they came from third-party uploaders wanting to share episodes of their favorite shows more freely. Muzzey was infuriated: he had previously pursued a large TV production company based in China through a lawyer years ago because some of his music ended up being used on their programs—unlicensed. The case was pursued by the Chinese arm of the law firm and ended up in an out-of-court settlement that netted Muzzey precisely zero dollars. “I didn’t realize how expensive it was to use a law firm like that,” he says. But he had thought that would be the end of his need to pursue legal action in China. It turned out it wasn’t.

Through the third-party uploads, Muzzey was able to match back the use of his music to certain TV shows, then to specific episodes. That led him to the official uploads that CCTV would occasionally post themselves on YouTube. “I found quite a few usages,” he says. “My music was in anything from silly reality TV shows to dating shows, but then also scripted dramas and movies.” He started using YouTube’s built-in copyright claim system to strike each one of the videos under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA); most of the videos had at least a million views already. (A copyright strike under the DMCA is treated differently to a ContentID claim on YouTube: ContentID claims can result in the offending material being taken down, or any profits made from it redirected to the rightful copyright owner. DMCA strikes result in warnings against the channel owners.) At the same time, Muzzey also laid strikes against a handful of other Chinese TV networks.

That angered the TV network.

Muzzey hadn’t considered the chain of events that was set off every time he pressed a button to claim copyright over music used in a YouTube video illegally. It triggers an alert that gets passed through YouTube to the uploader, warning them that someone believes they’ve acted against the law. YouTube cautions uploaders alleged to have breached copyright rules through a three-strike system. Three strikes, and your channel is terminated. For rank-and-file YouTubers, the strikes can pile up quickly. But, according to Muzzey, YouTube “do[es] acknowledge that if it’s a highly monetized YouTube partner, or one of their premium uploaders, that uploader gets something of a grace period to resolve the problem.” YouTube provides seven days to members of its YouTube Partner Program to rectify the situation, during which time the channel remains live.

In this instance, the scale of the strikes Muzzey was filing against CCTV blew through any grace period to resolve the problem. It was clear there had been a pattern of persistent, unrepentant copyright infringement of Muzzey’s works—alongside potentially hundreds of infringement incidents against other creators.

The sheer volume of copyright strikes ultimately compelled CCTV to engage with Muzzey.

reader comments

349