When Rosemary Brown was seven, a strange man in a cassock with long white hair appeared uninvited at her home in south London. No one thought to call the police. He said he was a long-dead musician and that he would return to make her famous when she was grown up. Only 10 years later when she saw a photograph did she realise that he was Franz Liszt.

Forty years later, in 1964, Liszt fulfilled his promise. By that time, Brown was widowed and supporting two children as a dinner lady.

As she sat at her piano, Brown said she became aware of her hands being taken over for a few bars and then, at Liszt’s instruction, she wrote down the notes. Other dead composers presented their proverbial calling cards. Chopin pushed her hands on to the right keys. Schubert tried to sing his compositions. Beethoven and Bach dictated the notes. Mozart, Rachmaninov, Brahms and Grieg also dictated new music to Brown. We don’t know if there was a queue of Mrs Brown’s boys waiting to avail themselves of her services, but I like to think so.

How did she communicate with these gentleman callers? After all, most didn’t speak English. In a 1969 BBC documentary, Brown explained: “Beethoven has obviously taken the trouble to learn English since he passed over.” So had the others. How convenient, sneered sceptics.

This weekend a selection of the piano music Rosemary Brown transcribed from the beyond by Rachmaninov, Beethoven and Liszt will be performed by pianist Siwan Rhys during the London Contemporary Music festival. The concert won’t, sadly, include the ending to Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony because, Brown recalled: “He told me he had decided to leave it as it was. He left it as a mystery and in a way it was more romantic as unfinished.” Nor, even more sadly, will there be performances of the 10th and 11th symphonies Beethoven wrote after his death that Brown transcribed.

The evening though will also offer the chance to witness the world premiere of a piece by German composer and organist Eva-Maria Houben, who has long explored the spectral presence of a sound as it decays into silence – the idea that in absence there is presence and what the blurb calls “the extraordinary, possessed vocal improvisations of Maggie Nicols.”

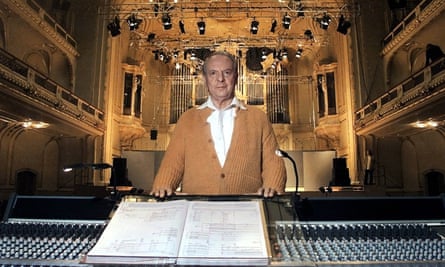

Music, of all the arts, lends itself to such mystical flights. “Sound is a haunting, a ghost, a presence whose location is ambiguous and whose existence is transitory,” wrote David Toop, professor of audio culture and improvisation at London College of Communication, in his book Sinister Resonance. “The close listener is like a medium who draws out substance from that which is not entirely there.” Many musicians have considered themselves mediums in this sense. Karlheinz Stockhausen believed he came from a planet orbiting the star Sirius and that he was put on Earth to give voice to a cosmic music that will change the world. “I do not make my music, but only relay the vibrations I receive…” he said in his 1968 autobiographical composition Aus den Sieben Tagen.

Rosemary Brown went on to become famous, as Liszt had predicted. She appeared on Oscar Peterson’s TV programme and the Johnny Carson Show. Leonard Bernstein dined her at the Savoy and then played some of Brown’s transcriptions, being especially thrilled by her Rachmaninov. Colin Davis asked her to inquire of Berlioz about the tempi in Les Troyens. She claimed to have communed with spirits including Einstein, Shaw, Jung and Bertrand Russell – which must have surprised the last of these since in his essay Do We Survive Death? Russell had concluded that we don’t.

Was she a fraud? The late composer Ian Parrott argued not. He believed she wasn’t clever enough to fake what she transcribed, he told the BBC documentary. “In my view,” Parrot wrote in her Guardian obituary in 2001, “the limitations of her training [she took a few piano lessons] left her unfettered by too much formal apparatus, and so better placed to receive music from others.” Liszt apparently told Brown as much: She related him telling her “… a musical background would have caused you to acquire too many ideas and theories of your own. These would have been an impediment to us.”

Here’s another theory. Maybe Brown was too clever to be detected by Parrott’s musicological radar. Perhaps she soft-pedalled her musical training and in reality composed pastiches of dead white men’s music, rather than passively channelling their posthumous compositions. So argued musicologist Dennis Matthews, writing in the Listener in 1969.

What’s less well known is that Brown also made psychic paintings too. In the BBC documentary, she shows off artworks she did under the guidance of Vincent van Gogh, Samuel Palmer, William Blake and JMW Turner. These dead masters guided her hands to produce what, to me, look like mediocre pastiches of their styles.

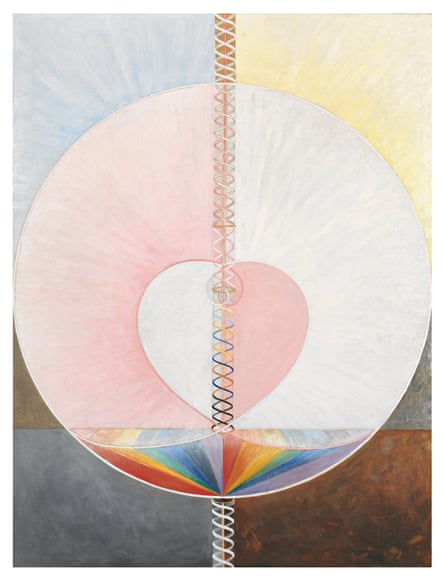

This is striking since several women artists have also been mediums, or channelled spirituality in their work - think of Leonora Carrington, Marina Abramović or Juliana Huxtable. Hilma af Klint, subject of a current retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Gallery, was a Swedish medium who, like Rosemary Brown, was sometimes controlled by spirits: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force.” She claimed to be directed by a force that would literally guide her hand as she painted, though unlike Brown that force was not that of a famous dead artist.

While Rosemary Brown might be best thought of as a pasticheur of dead white men’s music, Klint used automatic drawing and painted forms that the world was not quite ready for. In her will, Klint stipulated that her abstract works were not to be revealed to the world until 20 years after her death, and so her sister squirrelled 1,200 paintings away in her studio, waiting for the moment the public was ready for them. Judging by extraordinary response to the Guggenheim survey of her abstract paintings, significantly called Paintings for the Future, which has attracted 600,000 visitors making it the most visited in the museum’s history, we finally are.

Igor Toronyi-Lalic, the LCMF’s artistic director, has an intriguing perspective. He suspects that Klint painted what she really wanted to – her spiritually infused abstract works – under the cover of magic.

As for Rosemary Brown’s music, questions remain. Why did she only channel male composers? Surely Barbara Strozzi or Ethel Smyth might have enjoyed dictating new works to her from beyond the grave? And if she really was a fraud who actually composed all these works herself, why did she not write her own music? Surely that would have been more radical. If only there were some way we could contact her on the other side to get the answers …

In the meantime, why is Brown’s music worth a public performance? Toronyi-Lalic suggests that, like Klint’s abstract paintings, her piano pieces were radical breakthroughs by an underestimated artist. “The genius of these works is that they move music into conceptual art territory far ahead of anyone else. In that the works emphasise and prioritise the context, the reception, the origin story, the nature of reality and time itself over the sound. Whenever we listen to a work we are absorbing all this information but composers and critics and musicologists pretend it’s just about notes. She’s the first to say it’s so much more than about the notes.”

He concedes that it is not clear that, if all this is true, Rosemary Brown knew what she was doing. If she was a genius, then perhaps she didn’t know she was. “The fact that we don’t know whether she did this consciously or not makes the work all the more intriguing and beguiling.”

Maybe she wasn’t a genius, though, but a fraud. Toronyi-Lalic doesn’t dismiss the possibility. Yet even if she did deceive the world, passing off her work as as original works by late, great composers, Brown’s music is worth listening to. “Just at the level of improvisation – if that’s what we think it is – it’s amazingly fluent and shows a level of skill mixed with mischief that is pretty inspiring and astonishing.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion