5 February 1827

BEETHOVEN: We regret to learn, that the greatest musical genius of the present age, Ludowig Von Beethoven [sic], is, by this time, probably no more. He has just completed his 56th year. It appears that a Mr. Stumpff, of Vienna, from a noble desire to testify the high esteem he entertains for him, procured, at a very great expense, the entire Works of Handel, in forty volumes folio, Arnold’s excellent edition, handsomely bound, and sent them as a present to Beethoven. They were delivered to him free of any expense; but Beethoven at the time was laid up with dropsy in the abdomen, and though the operation of tapping had been performed, his physicians have pronounced him to be in extreme danger; he pointed his finger to Handel’s Works, and said, with feeling and emphasis – “That is the true thing.” He signed his name very legibly to the document, acknowledging the receipt of Handel’s Works.

23 April 1827

We find, in Russell’s Tour in Germany, the following account of the celebrated musical composer, Beethoven, whose recent death, in circumstances of poverty and distress, alleviated only by English charity, has attracted so much notice. The author seems to have met with him in 1822:

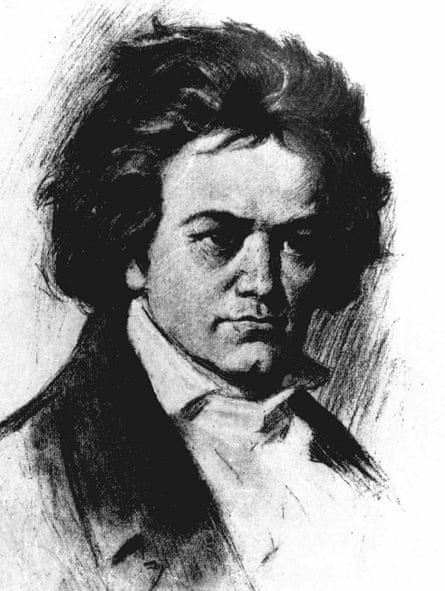

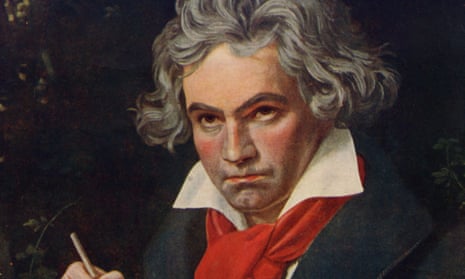

“Beethoven is the most celebrated of the living composers in Vienna, and, in certain departments, the foremost of his day. His powers or harmony are prodigious. Though not an old man, he is lost to society, in consequence of his extreme deafness, which has rendered him almost unsocial. The neglect of his person which he exhibits gives him a somewhat wild appearance. His features are strong and prominent; his eye is full of rude energy; his hair, which neither comb nor scissor seem to have visited for years, overshadows his broad brow in a quantity and confusion to which only the snakes round a Gorgon’s head offer a parallel.

His general behaviour does not ill accord with the unpromising exterior. Except when he is among his chosen friends, kindliness or affability are not his characteristics. The total loss of hearing has deprived him of all the pleasure which society can give, and perhaps soured his temper. He used to frequent a particular cellar where he spent the evening in a corner, beyond the reach of all the chattering and disputation of a public room, drinking wine and beer, eating cheese and red herrings, and studying the newspapers.

One evening a person took a seat near him, whose countenance did not please. He looked hard at the stranger, and spat on the floor as if he had seen a toad; then glanced at the newspaper, then again at the intruder, and spat again, his hair bristling gradually into more shaggy ferocity, till he closed the alternation of spitting and staring, by fairly exclaiming, ‘What a scoundrelly phiz!’ and rushing out of the room. Even among his oldest friends, he must be humoured like a wayward child.

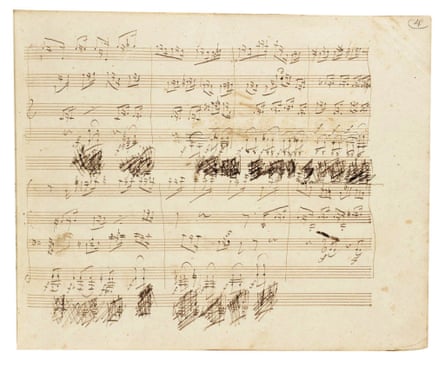

He has always a small paper book with him, and what conversation takes place is carried on in writing. In this, too, although it is not lined, he instantly jots down any musical idea which strikes him. These notes would be utterly unintelligible, even to another musician, for they have no comparative value; he alone has in his own mind the thread by which he brings out of this labyrinth of spots and circles the richest and most astounding harmonies. The moment he is seated at the piano, he is evidently unconscious that there is anything in existence but himself and his instrument; and considering how very deaf he is, it seems impossible he should hear all he plays. Accordingly, when playing very piano, he often does not bring out a single note. He hears it himself in the ‘mind’s ear.’ While his eye, and the almost imperceptible motion of his fingers, show that he is following out the strain in his own soul through all its dying gradations, the instrument is actually as dumb as the musician is deaf.

I have heard him play, but to bring him so far required some management, so great is his horror of being any thing like exhibited. Had he been plainly asked to do the company that favour, he would have flatly refused; he had to be cheated into it. Every person left the room, except Beethoven and the master of the house, one of his most intimate acquaintances. These two carried on a conversation in the paper book, about bank stock. The gentleman, as if by chance, struck the keys of the open piano, beside which they were sitting, gradually began to run over one of Beethoven’s own compositions, made a thousand errors, and speedily blundered one passage so thoroughly, that the composer condescended to stretch out his hand and put him right. It was enough; the hand was on the piano; his companion immediately left him, on some pretext, and joined the rest of the company, who, in the next room, from which they could see and hear everything, were patiently waiting the issue of this tiresome conjuration.

Beethoven, left alone, seated himself at the piano. At first he only struck now and then a few hurried and interrupted notes, as if afraid of being detected in a crime; but gradually be forgot every thing else, and ran on during half an hour, in a phantasy, in a style extremely varied, and marked, above all, by the most abrupt transitions. The amateurs were enraptured; to the uninitiated is was more interesting, to observe how the music of the man’s soul passed over his countenance. He seems to feel the bold, the commanding, and the impetuous, more than what is soothing or gentle. The muscles of the face swell, and its veins stand out; the wild eye rolls doubly wild; the mouth quivers, and Beethoven looks like a wizard, overpowered by the demons, whom he himself has called up.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion