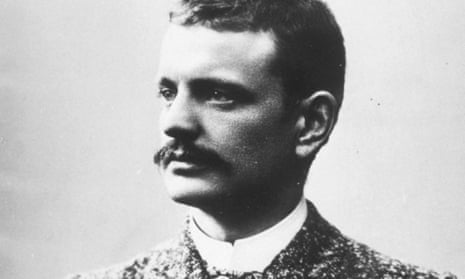

The Liverpool Orchestral Society’s Concert of Saturday was another of those refreshingly new experiences that one has learned to expect from this organisation. Sibelius’s First Symphony and his tone-poem Finlandia had been given before by the same Society, under Mr. Granville Bantock, at a concert in March of the present year, but an isolated performance of music so novel as that of Sibelius really gives one very little insight into it. It was good to have the works repeated, while special interest attached to the hearing of them under the bâton of the composer himself. Sibelius had intended to be present at the March concert, but was prevented at the last moment from coming over; this time Mr. Bantock was fortunate enough to secure him.

It is the first visit of Sibelius to England, and last Saturday’s was his first public appearance in this country. English knowledge of him rests solely upon the performance of two or three works of his in London, a solitary performance of his Second Symphony by Dr. Richter in Manchester last season, and the two Liverpool concerts. His work is fairly considerable in quantity, and includes two symphonies, some suites and symphonic poems, the first Finnish opera, and a number of songs. He is now working at a third symphony, a new symphonic poem based on a Finnish mythological subject, and a work that should excite exceptional interest both in Finland and abroad, the nature of which, however, he desires should not be made public at present. He is still a young man; he attains his fortieth year on the 8th of the present month.

The Symphony played on Saturday was his first, apparently written in 1899. The impression it makes on one is the same as that made by the Second Symphony – that here we have a man really saying things that have never been said in music before. It may be that a compatriot of Sibelius would not feel the perfect newness of it with the same force; we cannot be certain, that is, to what extent his outlook and his modes of expression may be shared by the other Finnish composers. But that does not alter the fact that for us here in England the bulk of his utterance is of an order quite different from anything we have hitherto met with in music. For this very reason it probably fails to take hold at once of a good many normal English listeners.

One of the most insidious aesthetic fallacies is that which states that music to be a universal language, comprehensible by all, irrespective of nationality or latitude. In reality it is not so. The reason why German, Russian, French, Italian, and English music make practically the same appeal to all normal Europeans is that we all live pretty well in the same intellectual and emotional atmosphere, and express ourselves pretty well in the same musical idiom. It is not so much that music is a universal language as that all the countries of Western Europe employ the one musical speech. As soon as we come to the music of a race with a radically different mental tradition from our own, we see at once how hard it is for us to pierce to the underlying emotion through the speech – how hard it is to get just the thrill the music awakes in men of its own race. It is only a receptive soul here and there, with some strange tincture of the East in him, that really catches to the full the beauty and the passion of the curious melodies of the Orient. And I can quite understand this Finnish music of Sibelius knocking in vain at the gate of many normal English ears.

For my own part, I have never listened to any music that took me away so completely from our usual Western life and it transported me into a quite new civilisation. Every page of it breathes of another manner of thought, another way of living, even another landscape and seascape than ours. For some of us it has an extraordinary fascination on this account, but we can quite realise that to others it is like a poem recited in a language they do not understand.

On purely technical lines one may make two or three criticisms of the symphony. Here and there I fail to follow the logic of the working-out; I cannot see much force in passages of imitation such as that on page 51 of the score – although I freely admit that a fuller knowledge of the symphony might put these things in a different light; and the frequent partiality for passages in thirds rather at savours of a mannerism.

But these minor cavils made, the symphony remains a remarkably fine piece of work. Its melodies are strikingly original; there is a faint suggestion of a phrase from the Pathetic Symphony in the slow movement, but the way in which the passage is handled as a whole proves that there has not been even a reminiscence of Tchaikovski’s [sic] melody. The thinking, almost all through, is intense and well sustained. The orchestration is full of novel and effective devices. But the point I wish to emphasise particularly is the newness of outlook that the music of Sibelius constantly shows – the sense it gives us that we are really listening to a new voice. Let anyone take as a specimen the last fifteen pages of the symphony – a piece of noble, impressive writing – and say, if he can, where else he has met with the same melody, the same scoring, the same general turn of thought. There is nothing of the same type in the music of any of the Western races.

Besides the symphony Sibelius conducted his little tone-poem Finlandia, a work of such unmistakable charm and such real freshness of utterance that one was not surprised to find it encored on Saturday. It is well within the powers of a small orchestra, and should become highly popular wherever it is played. Sibelius secured excellent performances of both the Finlandia and the symphony, though in the latter there was an occasional faultiness in the wood-wind, and the rapid pace of the scherzo did not always give the strings time to feel at home. He afterwards expressed himself as exceedingly pleased with the orchestra, and praised particularly the horn-playing of Mr. Paersch and the oboe-playing of Mr. Reynolds; the latter, he said, got the true oboe tone.

Mr. Bantock opened the concert with a spirited rendering of Dvorak’s Carneval Overture, and closed it with a brilliant performance of Berlioz’s Hungarian March. Miss Amy Castles sang the usual hackneyed barrel-organ air from Verdi’s Ernani and the superficial waltz-song from Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet. Her voice, though a little lacking in power, is of beautifully pure quality and extremely flexible. One could have discussed her performances at greater length had she sung anything worth discussing.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion