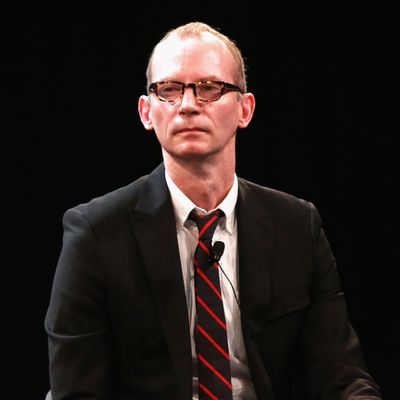

Charles Isherwood woke up on the morning of February 3 with one of the best jobs in the country: second-string theater critic for the New York Times. Around noon that day, he was summoned to the Times’s 40th Street office, along with representatives of his union, the NewsGuild of New York. They were called into a room with two senior editors and two other executives. Isherwood was confronted with nine of his own emails, which the paper claimed as evidence that the critic had violated ethical rules. Shortly afterward, he was escorted out of the building. In the two weeks since, no one who knows the details has spoken publicly, and those Times-watchers and Broadway people who don’t know can hardly talk about anything else. It’s not every day that a Times employee — never mind one of the most prominent theater critics in the country — is so publicly given the boot.

What follows is an attempt to get to the bottom of the story, based on conversations with more than a dozen people close to the events. The Times insists a crucial triggering incident is missing from the timeline; if so, it’s been very tightly held (maybe even from Isherwood), and we may not know what it is until he and the paper meet again, in arbitration.

In the twelve years of his suddenly truncated tenure, Isherwood had crossed the country scouting regional theaters and championing future stars like Tracy Letts and Stephen Karam. Along the way, he made a couple of theater-insider friends who the Times seems to feel affected his objectivity (and his loyalty). But the bigger issue may have been his rivals — the editors he clashed with, and especially Ben Brantley, the lead critic. When Isherwood arrived in 2004, he was under the impression that Brantley would soon retire. But as he stayed on, Isherwood grew increasingly, vocally frustrated, both with his number-two position and with the paper’s shrinking review space. According to a source, there were two early “dustups” between the critics, but, over the last five years, no contact at all.

Shortly after Isherwood’s firing, a notice was sent out to Times critics assuring them that this was a dismissal for cause — not a layoff. The following Tuesday, the paper posted a job listing for the position. Last week, Isherwood began pursuing arbitration. The fact that his dismissal resulted from a thorough search of his emails, which were handpicked for potential infractions, is extremely rare. Current and past employees remember it happening only once in recent years, for severe wrongdoing. They called it “extraordinary” and “inexplicable.”

Isherwood declined to comment for this story, but NewsGuild president Grant Glickson told me the Times had “drastically overreacted” in terminating him. “He has done nothing to warrant dismissal, unless remarking to a friend that he was disappointed that the Times was cutting its arts coverage was an offense.” The Times insists there was another incident that led to both the email search and the firing, but released only the following statement: “While we don’t comment on specific personnel matters, the scenario of someone simply being difficult or publicly negative about the Times or colleagues would never lead to the highly unusual step of a review of an employee’s email. Only something more serious would result in such an action.”

The emails brought up on that Friday (“Black Friday,” as Isherwood privately calls it) were communications with several Broadway producers — mostly the powerful movie and theater mogul Scott Rudin — as well as two publicists, Philip Rinaldi and Rick Miramontez. Isherwood rudely disparaged Brantley to Miramontez, and also, separately, to a friend at a ballet company. He also complained to the latter that Brantley had blocked him from reviewing Hamilton, even though he’d covered Lin-Manuel Miranda’s previous show, In the Heights.

Disparagement is a tricky area. Guidelines on collegial conduct — the “rules of the road” — are alluded to, but not specified, in the Times’s Ethical Journalism handbook, and Isherwood was charged with violating them. On its face, that certainly wouldn’t be cause for dismissal or email searches. “I just thought it was theatrical, the competition between them,” says Miramontez. “Spicy and energetic — I thought it was campy! If you go back to the glory days of thirty years ago, this is much ado about nothing.”

Isherwood also told a couple of producers about diminishing arts coverage at the Times, though they probably could have gleaned the same information by reading Deadline, which broke a story about consolidation in the arts pages last November. He was accused of threatening Rinaldi with a negative review; having not been invited to an early press performance, Isherwood had written him to say that he now had the flu and “didn’t know if he could do it justice” on a subsequent night. Rinaldi doesn’t remember that email at all. A joke to producer Jeffrey Richards about a legalistic correction Richards had asked for (on a story Isherwood hadn’t written) was perceived as somehow out of bounds.

Communications with Rudin were a bit more numerous and serious. Isherwood asked Rudin why his name wasn’t on a blurb in an ad; he also shared information about the paper’s thinking regarding year-end coverage of plays he wasn’t working on (while disparaging both Brantley and Hamilton). And a third email had to do with Stephen Karam’s The Humans, winner of the Best Play Tony for 2016. The Times highlighted an email to Rudin saying something along the lines of, “I’ll bat it out of the park,” on a Broadway review.

There are hard rules against promising favorable coverage at the Times and elsewhere. Rudin says this exchange with Isherwood was the result of a request that Isherwood re-review a play, period. The play had very recently transferred from an off-Broadway production, which Isherwood had raved about and Rudin hadn’t produced, and Times policy dictated that a second review so close to the first wasn’t mandatory. “Rudin was probably saying it’s important that you give it your best shot,” says Miramontez, who also handled publicity for the play — and calls this sort of interaction “a very common thing in our world.”

What’s “very common” in the course of social or professional exchanges can shade over into ethical infractions for a critic. This is especially so in Broadway theater, where producers often invest in multiple shows per season, but there can only be 41 running at a time — which means that, if you consider social relationships disqualifying, having one producer friend could cut you out of reviewing a good chunk of the season. (For the record, Isherwood’s reviews of these producers’ work ranged from negative to ecstatic.) It’s a small enough world that telegraphing forthcoming coverage in the paper of record risks spreading gossip like wildfire. But missing from the accounts we’ve heard about the emails is any evidence of favor-trading or real corruption. Everyone I spoke to said that while Isherwood could be very ornery, they couldn’t imagine him betraying the reader’s trust. “Charles isn’t that kind of person,” says Miramontez. “He’s very square and serious about his job.”

But what could possibly have caused the paper to start digging into his emails in the first place — something that almost never happens at the paper? Shortly after the firing, Times reporters worried that their employer was just trawling indiscriminately. Rumors began circulating. Some pointed to an arch Facebook post from the Tuesday before Isherwood was fired, in which he posted an online piece with the introduction: “This may never see print — welcome to the new world of the New York Times.” In fact, by the time of that post, the writing may have already been on the wall.

Even before Black Friday, Isherwood and his editor, Scott Heller, were having a very rocky week. They had two tiffs that may or may not have triggered the email search. (The Times maintains they didn’t.) First, there was a double review of two shows that Isherwood had seen in New Haven the week before — the same review Isherwood snidely posted on Facebook the next day. Heller was increasingly asking that regional reviews be packaged together as trend pieces — a tendency Isherwood viewed as diminishing his reach. Per Heller’s initial request, Isherwood tenuously linked the two plays together in a review that he filed on Monday, January 30. Then Heller told him their layout had changed and asked him to decouple the reviews into two shorter pieces. Isherwood refused.

The following day — the Tuesday of the snarky post — Isherwood had another argument with Heller. Months earlier, the critic had expressed his interest in profiling a big Broadway star of the current season. But after learning that Rudin had negotiated a place for a profile in another publication (which happened to be New York), he wrote to the producer to express his regret over not having the chance to write it for the Times. Rudin replied that the agreement had in fact fallen apart, meaning no other publication had an exclusive on it, and he’d be happy to help Isherwood secure the story. Isherwood took that news directly to Heller, but instead of getting the assignment, he was strongly admonished for “negotiating” with Rudin.

Rudin confirms the outlines of that narrative, and makes his sympathies perfectly clear. “I would always happily have Charles write anything he wanted about our work,” Rudin says. “I would not put anything or anybody I care about near Scott Heller” — which he also said in his email to Isherwood. Rudin is about as secretive about his antipathy for Heller as Isherwood is about his own for Brantley. “I think under him the section has become a joke,” Rudin says. “I think Charles doesn’t suffer fools and Scott Heller is a fool.” Rudin’s refusal to deal with Isherwood’s supervisor, while talking it down directly to the critic, couldn’t have sat well with the editors.

Someone close to decisions made at the Times rejected the idea that these incidents had motivated the search, without volunteering an alternative. But whatever the final straw, Isherwood hadn’t been happy for a long time, and he wasn’t shy about saying so. It wasn’t just a couple of emails — he took swipes at Brantley’s work everywhere from private conversations to public panels. “I think they were on a bit of a witch hunt,” says one theater veteran. “Any reason to get rid of this guy who was a very good critic with a very bad attitude.”

The battle lines in the Isherwood–Brantley turf war were familiar to anyone even mildly interested in New York theater. They had carved out their respective beats: Brantley would handle London plays and all the big Broadway shows, while Isherwood stalked regional theaters. If a play he had reviewed transferred to Broadway, he would follow it there. But Brantley always had first pick. Friends say Isherwood denigrated what Brantley loved — and not just Hamilton, which Isherwood felt he should have been allowed to review. Even in Times roundup features, he would mock Brantley-lauded revivals like Exit the King (which he said “proves that it’s possible to die of mugging”).

Brantley would occasionally rip into shows such as August: Osage County that Isherwood had championed in regional runs. But he was generally buttoned-up about their differences. Isherwood was a lot less so. To make matters worse, last year Isherwood asked culture editor Danielle Mattoon for a promotion to co-chief theater critic, an arrangement the art and movie critics share. He was turned down and wound up storming out of the office.

“Most of us were thinking, ‘What the fuck is wrong with you? You have the best job in the world,’” says a colleague. “If I had the role of second-string critic, where you could discover things and make a different kind of mark … I don’t think there was a lot of sympathy for the way he was behaving.”

Yet the dismissal still confuses this colleague, who notes, “It’s very rare for the Times to fire somebody. They could have shifted him to the municipal-bonds beat and the guild wouldn’t be able to do anything about it, so it is kind of shocking. But Charles had no rabbi left at the paper, nobody really protecting him, and maybe he was aware of that and gave up, or kept pushing the limits.”

Isherwood recently had drinks with another publicly fired Times employee, former executive editor Jill Abramson. She is as puzzled as anyone by what happened. “Ill feelings between critics at the Times was not unusual — it breeds competition, and sometimes anger,” she says. “But it’s hard for me to believe, knowing Charles as I do, that he would do something that was wrong.” She says that over gin and tonics — light on the tonic — she “assured him that the hurt would subside and that he would be perfectly, perfectly fine.”

Heller told colleagues he had nothing to do with Isherwood’s firing. It was Mattoon who attended the “Black Friday” meeting. (Both Heller and Mattoon declined to comment, referring queries to a Times spokesperson.) Another friend of Isherwood’s thinks Heller could at least have done more to heal the Isherwood–Brantley rift: “It would have been better for the two of them to have a relationship.”

Last month, the Times released a report recommending editorial streamlining and a decreased emphasis on print sections. Layoffs and buyouts are expected to follow, mostly targeting editors. It’s in that general context that some wonder if Isherwood’s firing was an easy way to get rid of someone making far above guild minimum, without having to pay a pension or severance. (The Times strongly denies any connection between the two situations.) The paper might also welcome the opportunity to hire a theater critic who’s younger, and maybe not a white man.

The ad for the position asked for candidates who’d work well with editors, interact with readers, and explore “new story forms.” It also included the line: “While a background writing about theater is a plus, it is not a prerequisite.” That doesn’t sound like a job for an old-school theater critic, or one quite so intimately familiar with the players as Charles Isherwood was. Rudin has some controversial opinions, but what he says about his associate would be hard to refute. “Charles was a highly respected and very well-regarded critic,” he says, “and it’s a huge loss to the paper and to the theater community. He championed a lot of shows that needed him. He made a difference in the ecology of the theater.”